FEATURE

Impact of Colloidal Silica Loading on Adhesive Properties and Film Morphology of High-Performance Waterborne Acrylic Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives

Part 1: Introduction and Experimental

Impact of Colloidal Silica Loading on Adhesive Properties and Film Morphology of High-Performance Waterborne Acrylic Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives

Part 2: Results and Discussion

By Kylie M. Kennedy, Ph.D., Research Scientist, Acrylic Adhesives; Joseph B. Binder, Ph.D., Senior Research Scientist, Acrylic Adhesives; Edward L. Lee, Ph.D., Research Scientist, Acrylic Adhesives; Johnpeter Ngunjiri, Ph.D., Research Scientist, Core R&D Analytical Sciences; Michael A. Mallozzi, R&D Technician Leader, Acrylic Adhesives; William DenBleyker, R&D Technician, Acrylic Adhesives, The Dow Chemical Co., Collegeville, Pennsylvania

This paper was honored with the 2024 Carl Dahlquist Award at the Pressure Sensitive Tape Council's Tape Week 2024.

Abstract

Many high-performance pressure-sensitive adhesive (PSA) applications are dominated by solventborne and radiation-curable PSAs because they can achieve greater cohesive strength and heat resistance than waterborne technologies. However, waterborne emulsion PSAs provide many advantages such as high solids, low cost, safe handling, and environmental benefits. With these advantages in mind, industry and academia alike have sought to close performance gaps between waterborne emulsion PSAs and other technologies, especially by achieving high adhesion in combination with high shear and high-temperature resistance.

Inorganic nanofillers have been incorporated in situ during polymerization or as post-polymerization additives to improve the mechanical properties of waterborne acrylic adhesives. The method of introduction and the resulting filler-filler interactions and networks within the dried film are extremely important to the final mechanical properties. In this study, colloidal silica (Levasil CT14 PNM) (CS) and an experimental nanoparticle (EN) filler were added to a bimodal particle size, high solids (>60% total solids), poly(butyl acrylate)-co-(methacrylic acid) waterborne PSA emulsion at 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 wt% on a solids on total weight of latex basis. These formulations were coated on 2-mil PET to prepare laminates under industrially relevant drying conditions at two different coating weights. PSA performance (peel adhesion, loop tack, shear resistance, and shear adhesion failure temperature (SAFT)) were assessed on both high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and stainless steel (SS) substrates. Notably, CS addition improved the shear resistance while maintaining peel adhesion. Furthermore, the SAFT increased from 100°C to over 170°C with CS addition. The EN additive also improved shear resistance and SAFT, while maintaining adhesion. Interestingly, loop tack was also improved on both HDPE and SS substrates at higher coating weight. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) of the surface of the dried films was used to probe how the morphology may relate to PSA performance.

For Introduction and Experimental, see ASI’s June edition.

Results and Discussion

Preparation of Blends and Physical Properties

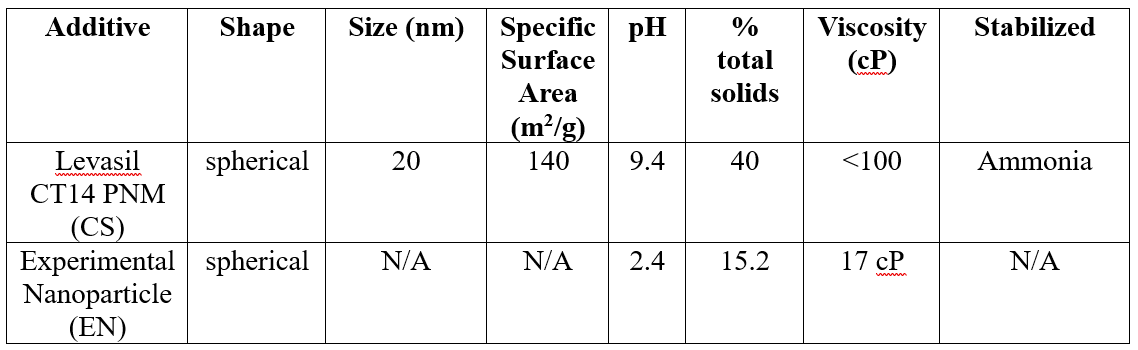

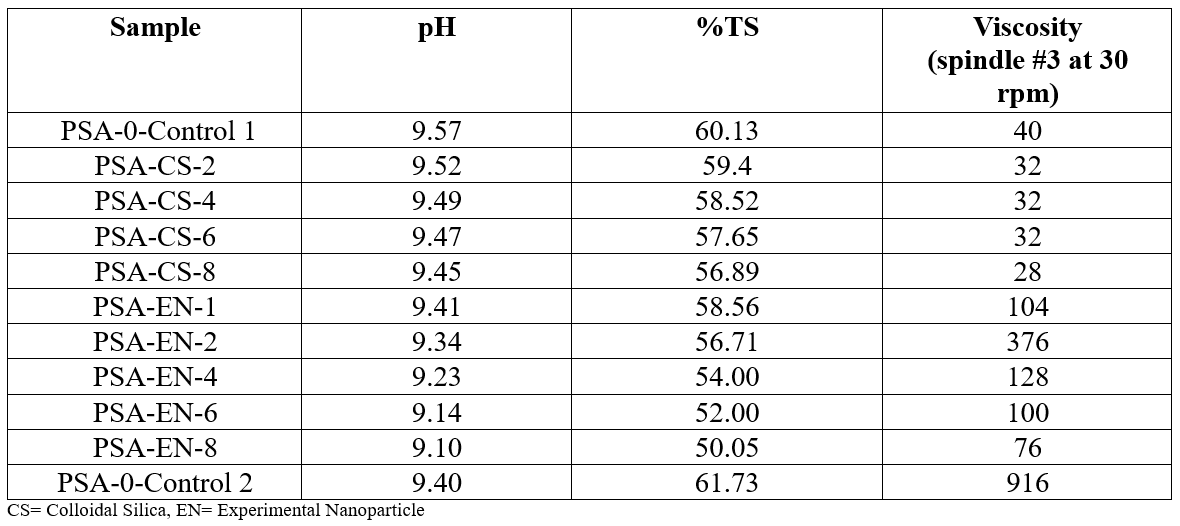

Levasil CT14 PNM was graciously provided by Nouryon and will be referred to as colloidal silica (CS). The CS is an alkaline, aqueous dispersion of colloidal silica that is approximately 40% solids by weight (Table 1) and is spherical in nature with an approximate particle diameter of 20 nm (Table 2). The silica dispersion is ammonia stabilized at pH 9.4. The surface of the colloidal silica particle contains hydroxyl-silanol groups, making the particles very hydrophilic. Further, the CS can be considered almost like small glass particles because the melting point of SiO2 is about 1650 °C and should remain as discrete particles even at high temperature (Nouryon website). The EN particles do not contain the same surface moieties but are comparable to the CS in size. The CS and EN particles were added to the respective control latex dropwise with overhead mechanical stirring. The pH of the latex was adjusted to pH 9.5 to prevent coagulation of the latex on addition of the nanoparticle additives. The mixtures were stirred for 10 minutes, and general properties of the blends are visible in (Table 3). The resulting blends have solids range from 50-60% total solids. The latex formulations were then direct coated onto 2-mil PET and dried at 80 °C for 15 minutes to a target coat weight of 50 or 18 gsm. The laminates were closed with release liner RP-12 and conditioned in a controlled temperature room (23 °C, 50% RH) for 24 hrs. Loop tack, peel, shear resistance, and SAFT were measured on the PSAs.

Table 2: Comparison of Latex Additives

Table 3. Characterization of PSA and PSA-Nanoparticle blends

PSA Performance of PSA and PSA-Colloidal Silica (CS) Nanoparticle Blends

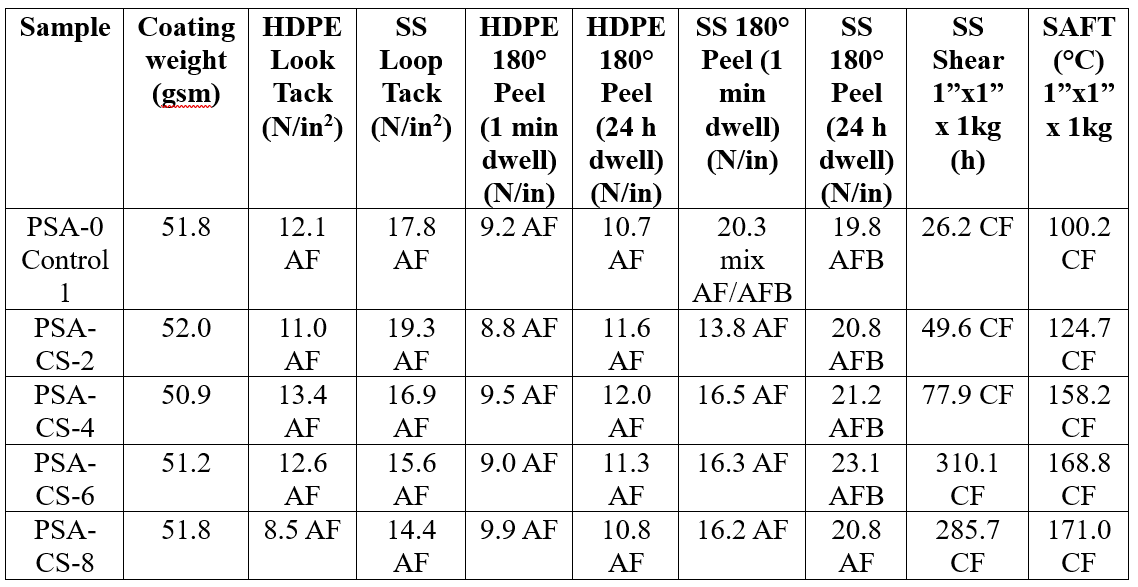

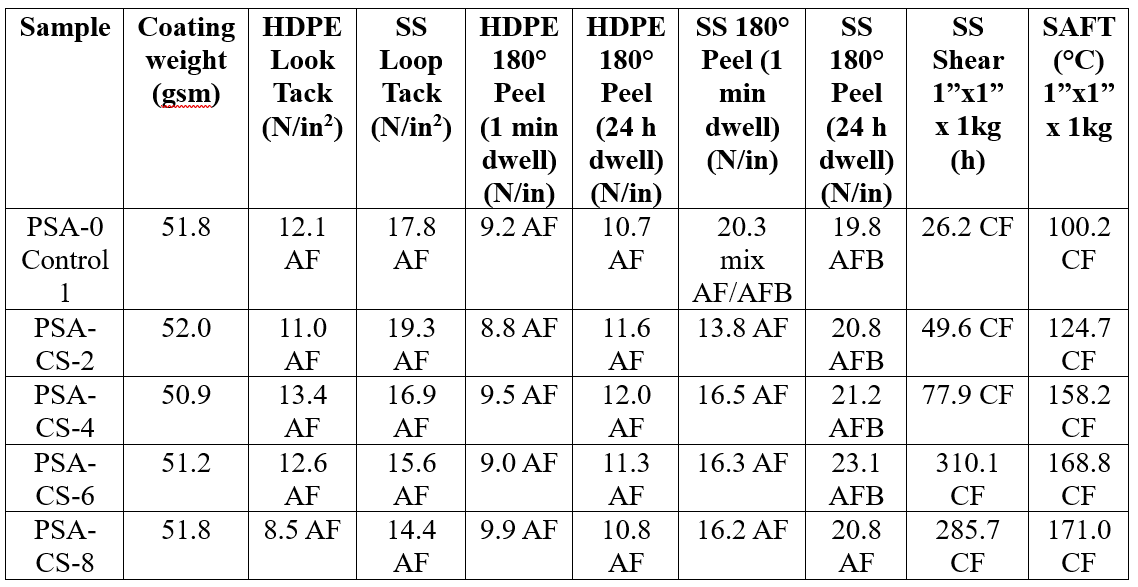

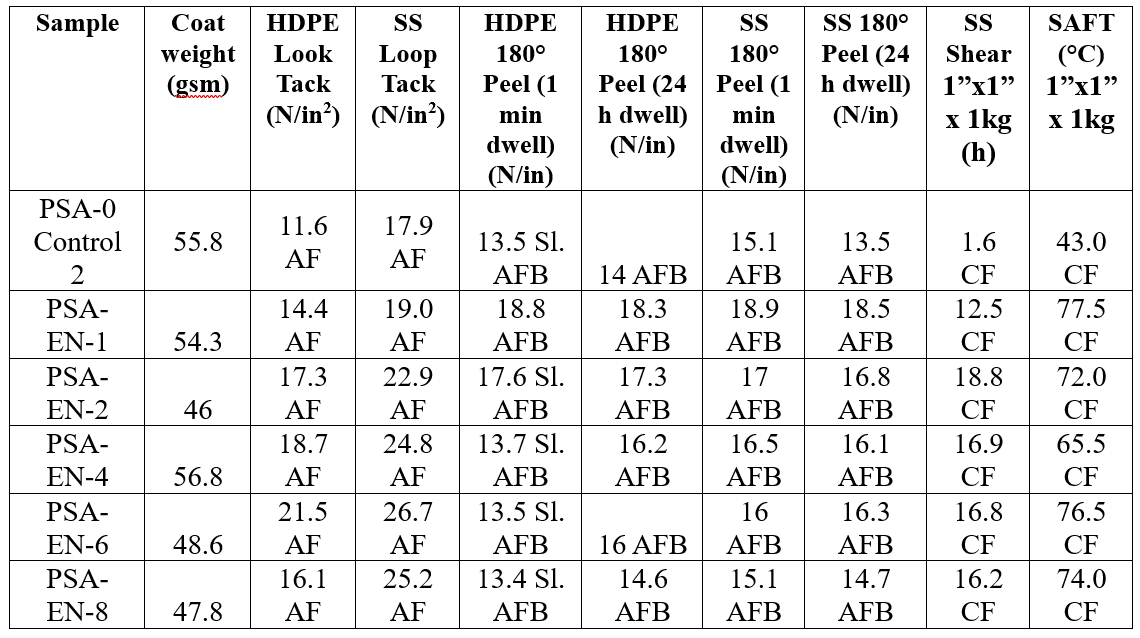

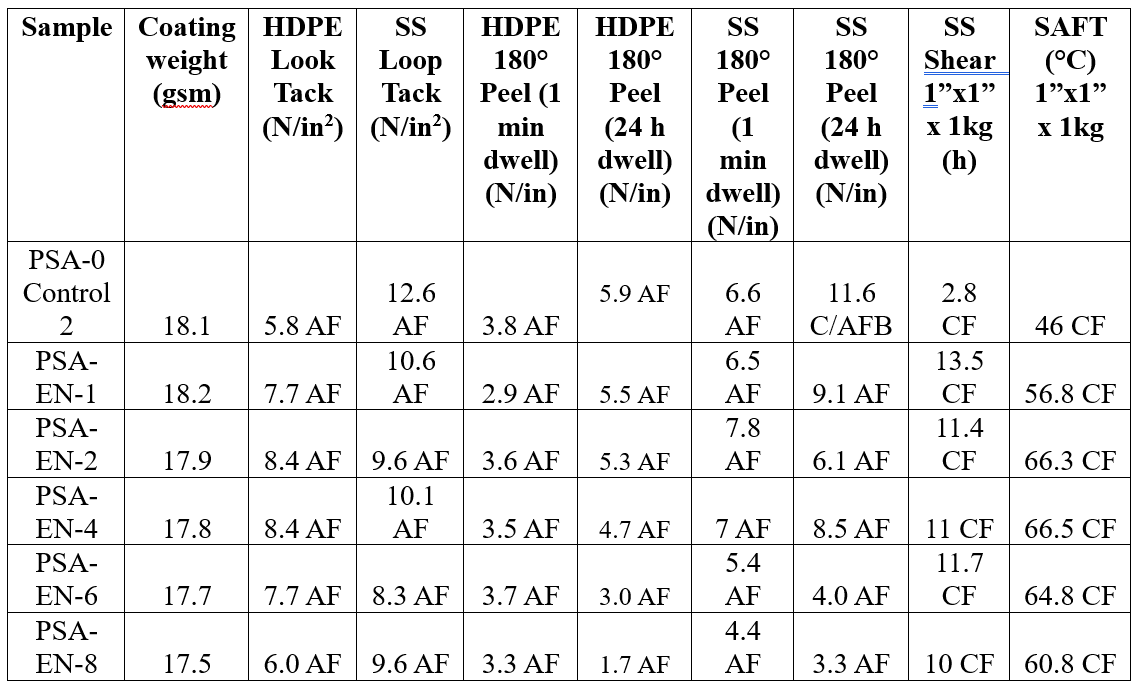

In general, the peel adhesion properties of the CS-containing adhesives coated at target 50 gsm (Table 3) and 18 gsm (Table 4) coat weights were similar to the control sample for all filler loading levels on HDPE and SS substrates. Notably, however, the shear and SAFT were significantly improved from 26 hours to up to 300 hours and from 100 °C to over 150 °C, respectively, on SS for the 50 gsm laminates with similar trend at lower coating weights. It is well known that the high number of hydroxyl surface groups interact with other chemical groups (i.e. oxide, hydroxyl or carboxylic acid groups) on multiple substrates, which would improve not only filler substrate interactions but also filler-latex interactions in the dried film.34,35 Loop tack trended downward on the addition of greater loadings of CS at high coating weight (Table 4). The CS imparts hydrophilicity to the PSA, and this can reduce tack by causing more moisture to be retained by the surface during drying. These results demonstrate the potential benefits of colloidal silica for increased cohesive strength and high-temperature applications.

Table 4. PSA performance of PSA and Levasil CT14 PNM (spherical colloidal silica) blends at high coating weight (target 50 gsm).

Table 5. PSA performance of PSA and Levasil CT14 PNM (spherical colloidal silica) blends at lower coating weight (target 18 gsm).

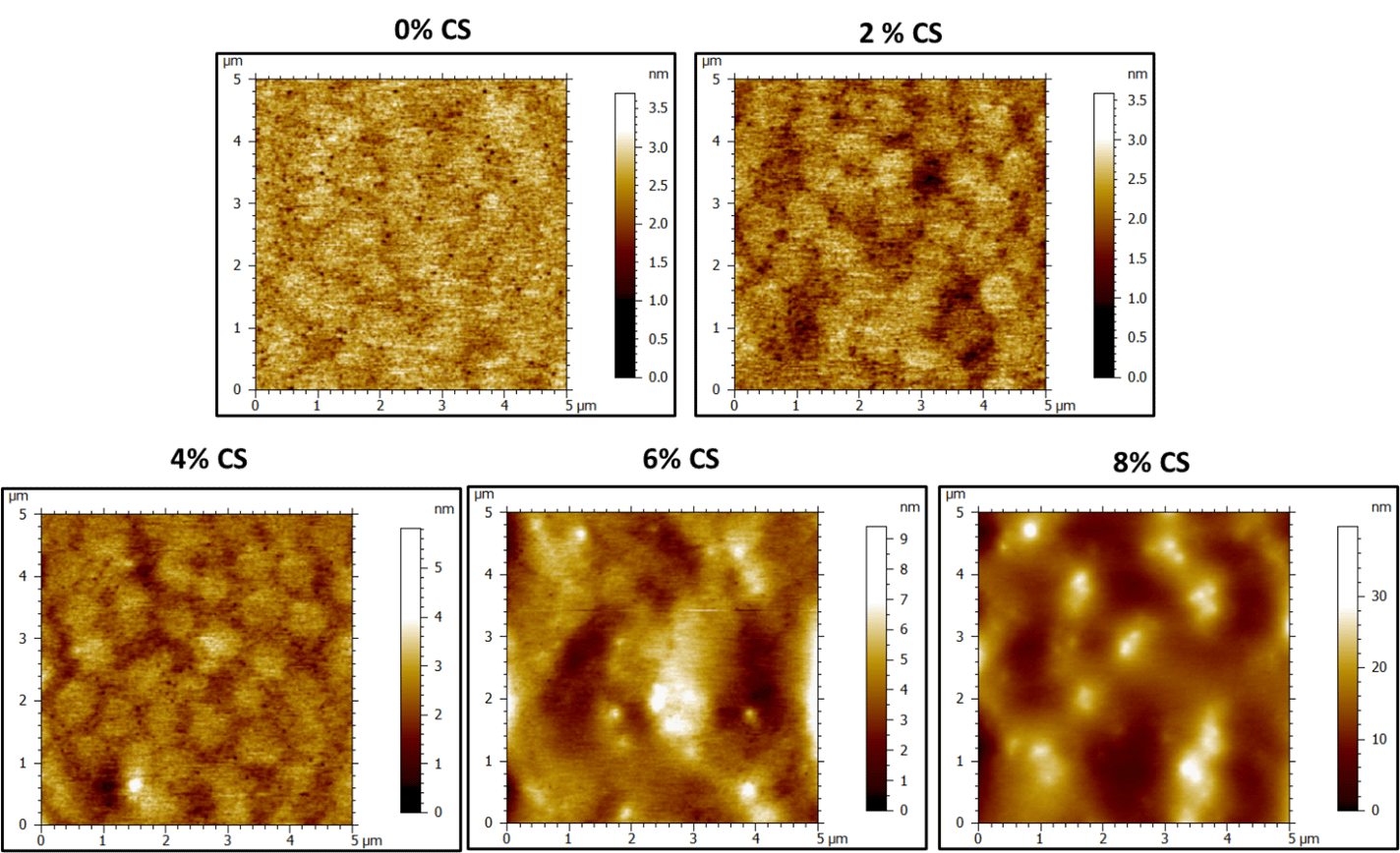

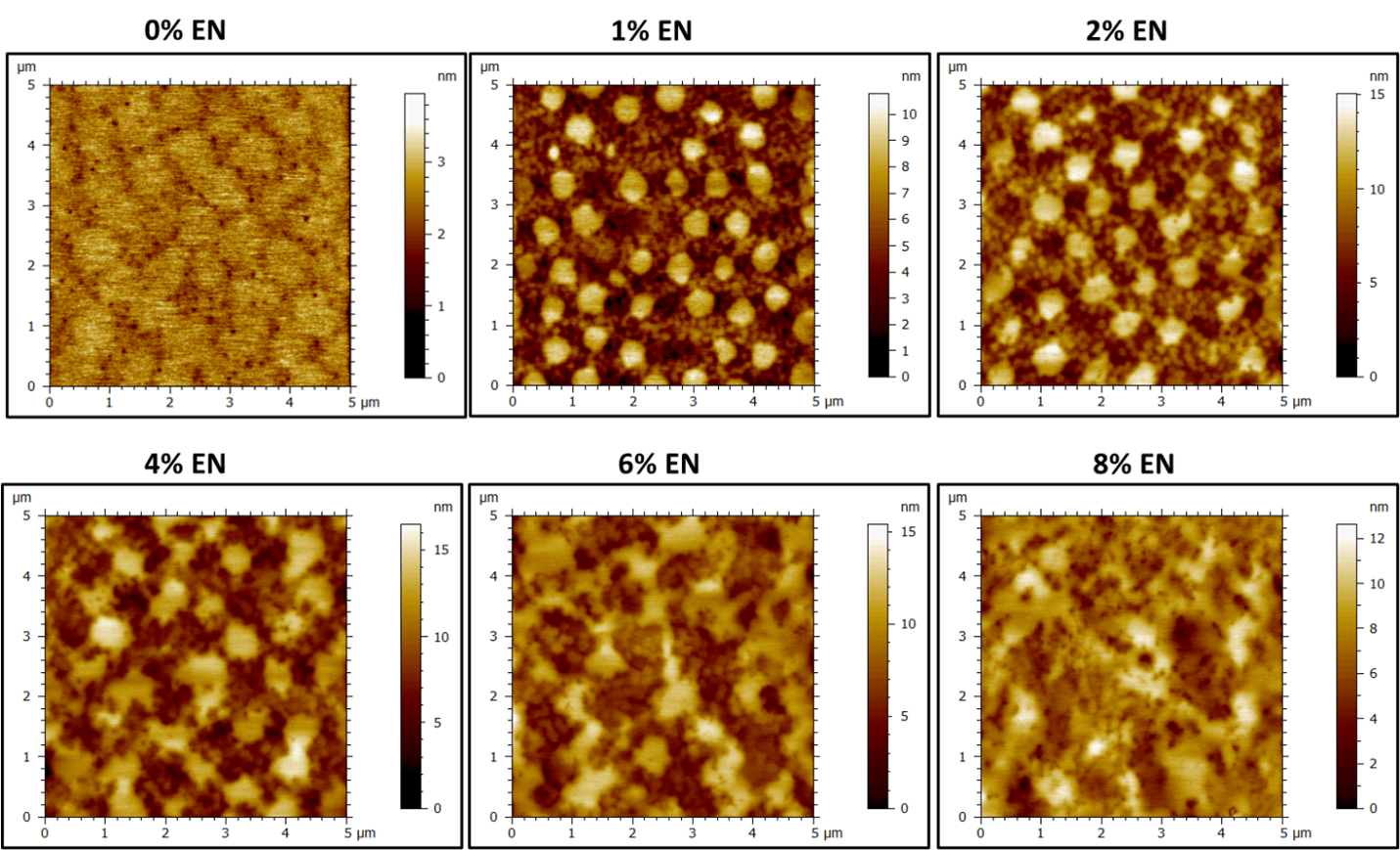

Atomic Force Microscopy of PSA-CS Dried Films

AFM tapping mode was used to analyze the surface morphology of the 50 gsm PSA films and the height and phase images are observed below (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Unfortunately, cross-sectional analysis was challenging due to the soft nature of the films. Freshly peeled PSA coatings on PET samples were analyzed in tapping mode. The 0% CS height images (control) show a soft film where individual latex particle boundaries are difficult to divulge (Figure 1). There are some dark red spots that are hypothesized to be surfactant pools between latex particles or other hydrophilic components of the latex that bloom to the surface upon drying. History of individual latex particles in the 0% CS film are easier to see in the phase images. Furthermore, akin to the height image, the bright, small spots are indicative of some surfactant or water-soluble species migrating to the surface on drying. These bright spots tend to be located at the interstitial spaces between the soft, latex particles and impede formation of a truly homogeneous film.

Upon adding CS, particle boundaries between soft and hard phases are more obvious. This is especially the case between 2-6% CS loading. Soft latex particles on the order of ≈800-900 nm are visible on the surface of the film with a smaller, harder phase located in between the soft latex particles. It is difficult to see, but there also appears to be some soft (darker) phase within the harder (brighter) phase (Figure 2, 4-6% CS). The control latex is a bimodal latex. Increasing the amount of CS appears to change the distribution of the smaller and larger latex particles at the surface. Large particles dominate the surface when there is no CS. Upon addition CS, particles attributed to the smaller mode become visible and are dispersed within the “hard” CS phase. From the height images, the soft latex particles are slightly higher and lead to nanoscale surface roughness (Figure 1.).

The height images reveal the height variation continues to increase as the amount of CS is increased, indicating increased surface roughness with high CS loading (Figure 2 and Figure 5). This roughness, in addition to hydroxyl-silanol functionality from the CS would lead to improvement in shear. The colloidal silica (brighter) regions on the periphery of the soft latex particles would also lead to mechanical reinforcement, which resulted in improved shear resistance and SAFT. At high CS loading (8%), it appears, that the morphology becomes more disordered at the surface, with agglomerated phases of CS (Figure 2). These results correlate well with the PSA performance data in that some properties started to drop off at 8% loading, indicating 2-6% CS as an optimal amount of additive to tune adhesion/cohesion. We suspect that a percolated structure of continuous hard and soft domains leads to improvement of shear, without considerable loss in adhesion, but this would only be confirmed by film cross-sectional analysis. The glassy nature of the CS particles allows them to remain phase separated during film formation, but they also contain sufficient affinity to the surface of the soft latex particles due to hydroxyl-silanol — carboxylic acid hydrogen bonding, which would improve strength at filler-latex boundaries.

Figure 3. AFM height images of dried latex films (50 gsm) containing 0-8% colloidal silica.

Figure 4. AFM phase images of dried latex films (50 gsm) containing 0-8% CS. Dark regions indicate "softer" material and brighter regions are composed of “harder” material.

PSA Performance of PSA and PSA-Experimental Nanoparticle (EN) Blends

Building on the learnings above, EN was synthesized and added to a control latex from 0-8 wt%. The EN are phase-segregated from the latex particles in the initial PSA suspension. We hypothesize that they would remain separated from the latex polymers during film drying and latex coalescence. This phase separation should allow the EN filler to effectively fill in the PSA voids that occur during water evaporation, thereby filling gaps between latex particles that are unable to fully coalesce. We hypothesized this would result in increased cohesion in the film as observed in films prepared from CS formulations. The size of the EN (approximately 26 nm in diameter) and high surface area are also advantageous in that the EN are small enough to not impede deformation and flow of the soft latex particles, akin to the CS particles.

The adhesion properties of the EN-containing latex samples exhibited increasing peel and tack performance with increasing additive level as compared to the control on HDPE and SS test substrates. While the overall adhesion properties were lower at lower coating weights, the thicker 50 gsm set showed the pronounced impact of the EN fillers on adhesion including 85% and 50% improvement (6 wt% EN) on HDPE and SS, respectively, for loop tack. Additionally, the peel adhesion of the EN-containing samples was as good or better than the control, and particularly, the thicker coating showed exceptional peel adhesion reaching ~15 N/in before backing failure with 1 minute dwell time, which were not achievable with CS particles. The SS shear and SAFT of the EN-containing adhesives showed remarkable improvement versus the control from 2 hours to over 10 hours and ~45 °C to 65–75 °C, respectively,which were consistent at both coating thicknesses.

Table 6. PSA performance of PSA and Experimental Nanoparticle blends at high coating weight (target 50 gsm).

Table 7. PSA performance of PSA and Experimental Nanoparticle blends at lower coating weight (target 18 gsm).

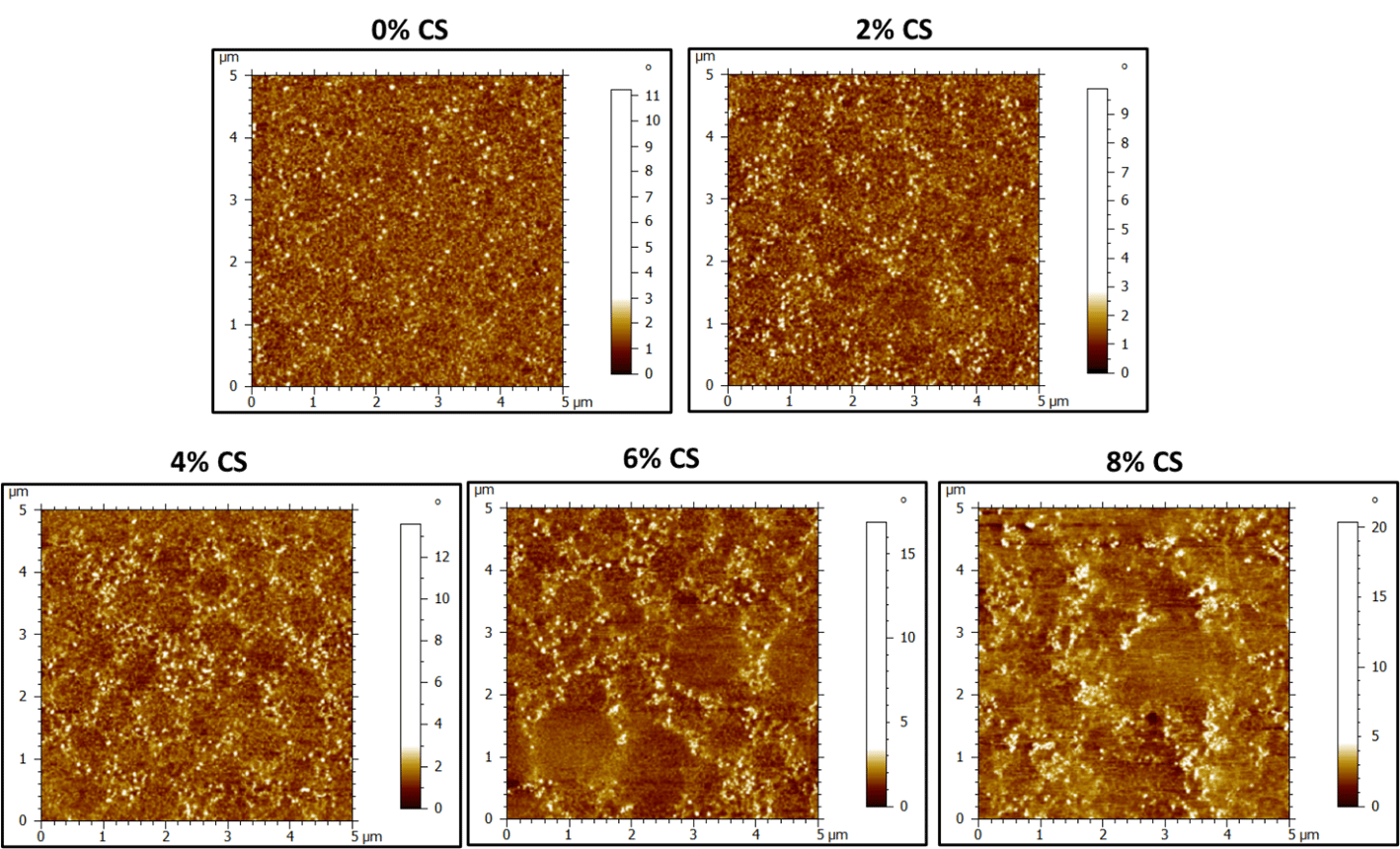

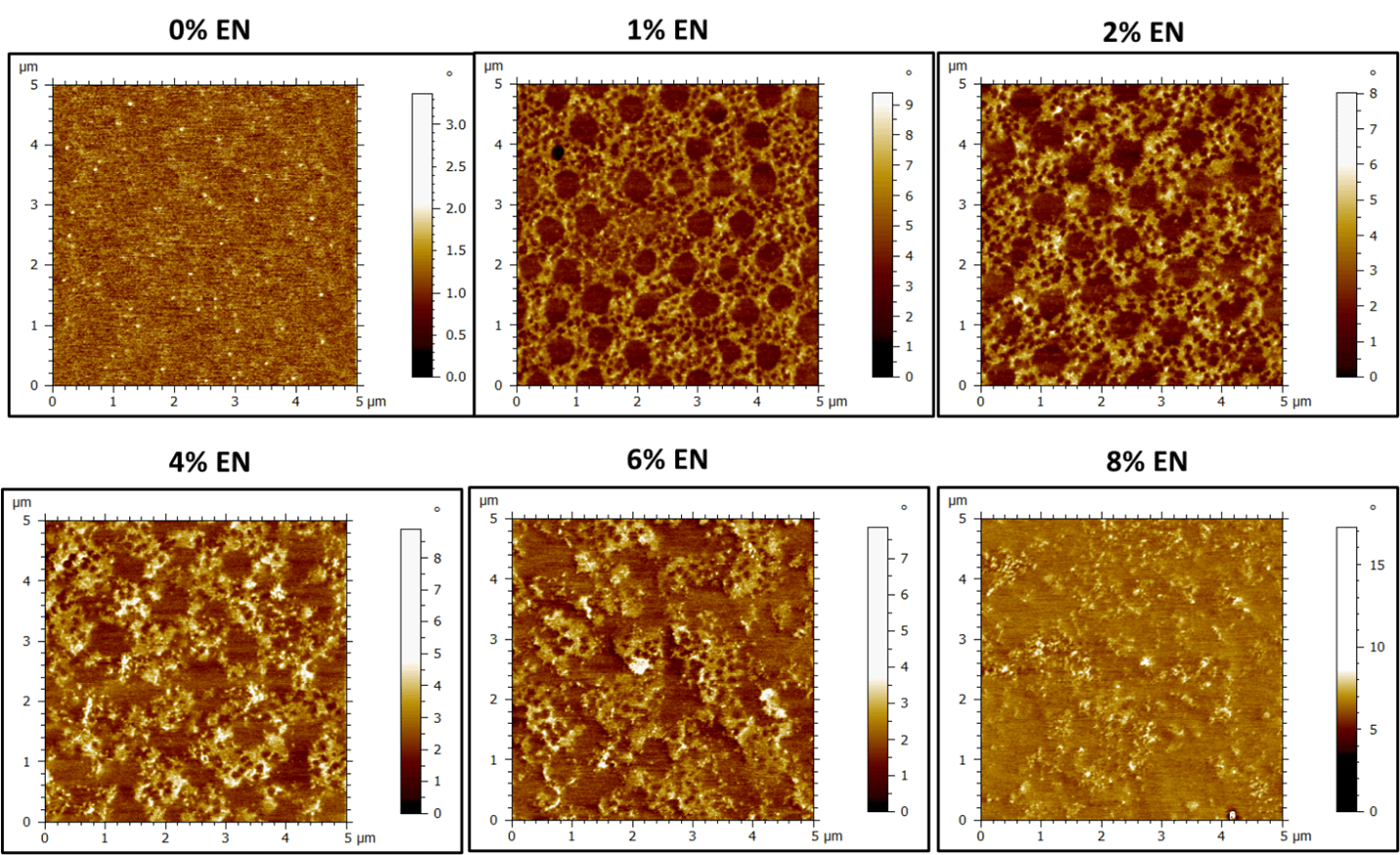

Impact of Experimental Nanoparticle Additive on Film Morphology

The height and phase images of the control latex (0% EN) show some history of the latex particle boundaries on the size order of 800-900 nm (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Again, smaller, brighter features (in phase images) are visible and likely correspond to small molecule materials (surfactants and other water-soluble agents) blooming to the surface on drying. Upon the addition of only 1% EN, there is a drastic change in surface morphology and regions of hard and soft material become more apparent (Figure 4). At 1% and 2 % EN loading, the larger latex particle mode is surrounded by a hard phase that contains regions of soft latex corresponding to the smaller latex particle mode. The hard phase consists of the EN and the smaller latex particles are evenly distributed throughout this phase. Like the CS example, addition of EN additive changes the distribution of latex particles at the surface from mostly large particles to a mixture of both small and large particles. At 4-6% EN loading, the films start to appear less uniformly ordered between soft and hard phases, with large aggregates of hard phase starting to dominate the surface. At 8%, there are no clear morphological trends, and the surface appears hard and disordered.

Like the CS blends, the surface roughness is also impacted by the addition of EN (Figure 3 and Figure 5). The image z-height increases from approximately 4 nm to 15 nm from 0-2% EN loading, with the soft latex particles protruding from the film surface. The distribution of the latex “bumps” is uniform, with approximately 1 µm spacing from large particle center to center at 1-2% EN loading; reflecting hexagonal close-packing of particles. The height and roughness of the film remains relatively constant above 6% EN, whereas with the CS the roughness continued to increase with increasing nanoparticle loading (Figure 5).

Figure 5. AFM height images of dried latex films (50 gsm) containing 0-8% EN.

Figure 6. AFM phase images of dried latex films (50 gsm) containing 0-8% EN. Dark regions indicate “softer” material and brighter regions are composed of "harder" material.

Coating Roughness

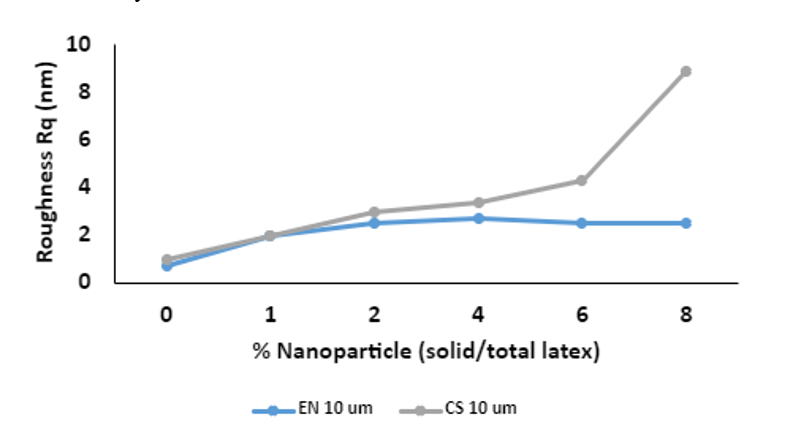

Coating roughness (Rq) was calculated from 10 µm2 images to capture both CS and EN particle contribution and the acrylic particle shapes at the surface. Roughness in the CS coatings continued to increase across the 0-8% loading levels. The EN coatings showed surface roughness up to 4% level and stayed somehow constant at 6% and 8%.

Figure 7. Surface roughness versus % nanoparticle additive measured and calculated from 10µm2 AFM images. The blue line relates to experimental nanoparticle (EN) loading and the grey line relates to colloidal silica (CS) loading.

Comparing Nanoparticle Additives

Both the CS and EN fillers increased shear resistance and SAFT performance.7 For the EN however, a notable improvement in loop tack was observed, especially in the 50 gsm films. We attribute differences in the loop tack to differences in how the additives interact at the latex-filler junctions. Optimal mechanical properties (i.e. balanced adhesion/cohesion) have been reported to occur when modifications result in an increase in the low-frequency modulus in the small angle regime in combination with significant softening and strain-rate-dependent behavior in the large-strain regime.7 It is hypothesized that both CS and EN additives impart a hard filler effect (i.e. increase in small strain modulus) that would improve shear resistance which is slow deformation process.7 The CS filler is hypothesized to have stronger surface interactions between the inorganic filler and latex particles, which could lead to increased elasticity as it is strained. In the case of the EN particles, it is hypothesized that there would be less viscoelasticity at intermediate strain but that weaker interfaces between EN and latex may allow a relatively high level of viscoelasticity at high strains, which would allow the formation of extended fibrils on debonding.7 This will be investigated in the future using rheological and tensile testing at various strain rates.

Conclusions

In this study, two types of spherical nanoparticles were added to waterborne PSA latex and the impact on PSA performance and film surface morphology were analyzed using industrial PSTC test methods and AFM. Colloidal silica (CS) increased both shear resistance and SAFT, while maintaining adhesion. Loop tack decreased at high loading of CS. When experimental nanoparticle (EN) was added to a control latex, improvement in shear resistance and SAFT were also observed, but loop tack was surprisingly improved. We suspect the differences in tack are due to the strength of the interface and any chemical interactions formed between the soft latex phase and the filler. This will be probed using rheology and tensile testing methods in future work. By AFM, in both cases, surface roughness increased with nanoparticle loading but was more drastically roughened with high loadings of CS. This surface roughness can improve shear. At loading generally below 6%, a difference in the distribution of soft latex particles is observed at the surface in both cases. Mainly, the larger latex particle mode is observed at the surface of control samples, and upon increasing the additive, the number of smaller latex particles is increased and distributed within the hard additive phase. This is especially apparent with the EN loadings at 1-2% where the hard EN phase contains evenly distributed spherical soft domains of latex. In both the CS and EN cases, it is hypothesized that a percolated network structure is responsible for good adhesion/cohesion balance at low to medium loadings of filler, although this can only be confirmed with cross-sectional analysis via AFM. Future work will entail investigation of how these nano-additives impart changes to the linear and nonlinear viscoelastic properties using rheology measurements and tensile testing.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dow Adhesives and Core R&D Analytical Sciences for their support of this work as well as PSTC for the opportunity to present it.

References

1. Tobing, S., Klein, A., Sperling, L. H. & Petrasko, B. Effect of network morphology on adhesive performance in emulsion blends of acrylic pressure sensitive adhesives. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 81, 2109–2117 (2001).

2. Czech, Z. & Milker, R. Development trends in pressure-sensitive adhesive systems. 2005 23, 0137–1339.

3. Mallégol, J., Bennett, G., McDonald, P. J., Keddie, J. L. & Dupont, O. Skin Development during the Film Formation of Waterborne Acrylic Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives Containing Tackifying Resin. J. Adhes. 82, 217–238 (2006).

4. Felton, L. A. Mechanisms of polymeric film formation. Int. J. Pharm. 457, 423–427 (2013).

5. Nollenberger, K. & Albers, J. Poly(meth)acrylate-based coatings. Int. J. Pharm. 457, 461–469 (2013).

6. Ribeiro, T., Baleizão, C. & Farinha, J. Functional Films from Silica/Polymer Nanoparticles. Materials 7, 3881–3900 (2014).

7. Bellamine, A. et al. Design of Nanostructured Waterborne Adhesives with Improved Shear Resistance. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 296, 31–41 (2011).

8. Yang, J. et al. The effect of molecular composition and crosslinking on adhesion of a bio-inspired adhesive. Polym. Chem. 6, 3121–3130 (2015).

9. Wahdat, H., Gerst, M., Rückel, M., Möbius, S. & Adams, J. Influence of Delayed, Ionic Polymer Cross-Linking on Film Formation Kinetics of Waterborne Adhesives. Macromolecules 52, 271–280 (2019).

10. Lee, J.-H., Shim, G.-S., Kim, H.-J. & Kim, Y. Adhesion Performance and Recovery of Acrylic PSA with Acrylic Elastomer (AE) Blends via Thermal Crosslinking for Application in Flexible Displays. Polymers11, 1959 (2019).

11. Czech, Z. Synthesis and cross-linking of acrylic PSA systems. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 21, 625–635 (2007).

12. Tobing, S. D. & Klein, A. Molecular parameters and their relation to the adhesive performance of acrylic pressure‐sensitive adhesives. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 79, 2230–2244 (2001).

13. Tobing, S. D. & Klein, A. Molecular parameters and their relation to the adhesive performance of emulsion acrylic pressure‐sensitive adhesives. II. Effect of crosslinking. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 79, 2558–2564 (2001).

14. Gurney, R. S. et al. Mechanical properties of a waterborne pressure-sensitive adhesive with a percolating poly(acrylic acid)-based diblock copolymer network: Effect of pH. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 448, 8–16 (2015).

15. Peruzzo, P. J. et al. On the strategies for incorporating nanosilica aqueous dispersion in the synthesis of waterborne polyurethane/silica nanocomposites: Effects on morphology and properties. Mater. Today Commun. 6, 81–91 (2016).

16. Kennedy, K. M. et al. Variation in adhesion properties and film morphologies of waterborne pressure‐sensitive adhesives containing an acid‐rich diblock copolymer additive. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 140, (2023).

17. Deplace, F. et al. Deformation and adhesion of a periodic soft–soft nanocomposite designed with structured polymer colloid particles. Soft Matter 5, 1440–1447 (2009).

18. Wang, T. et al. Waterborne, Nanocomposite Pressure‐Sensitive Adhesives with High Tack Energy, Optical Transparency, and Electrical Conductivity. Adv. Mater. 18, 2730–2734 (2006).

19. Yang, J., Zhang, Z., Friedrich, K. & Schlarb, A. K. Creep Resistant Polymer Nanocomposites Reinforced with Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 28, 955–961 (2007).

20. Wang, Z. D. & Zhao, X. X. Creep resistance of PI/SiO2 hybrid thin films under constant and fatigue loading. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 39, 439–447 (2008).

21. Zhang, Z., Yang, J.-L. & Friedrich, K. Creep resistant polymeric nanocomposites. Polymer 45, 3481–3485 (2004).

22. Novak, B. M. Hybrid Nanocomposite Materials—between inorganic glasses and organic polymers. Adv. Mater. 5, 422–433 (1993).

23. Zou, H., Wu, S. & Shen, J. Polymer/Silica Nanocomposites: Preparation, Characterization, Properties, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 108, 3893–3957 (2008).

24. Percy, M. J. & Armes, S. P. Surfactant-Free Synthesis of Colloidal Poly(methyl methacrylate)/Silica Nanocomposites in the Absence of Auxiliary Comonomers. Langmuir 18, 4562–4565 (2002).

25. Tiarks, F., Landfester, K. & Antonietti, M. Silica Nanoparticles as Surfactants and Fillers for Latexes Made by Miniemulsion Polymerization. Langmuir 17, 5775–5780 (2001).

26. Bourgeat-Lami, E. & Lang, J. Encapsulation of Inorganic Particles by Dispersion Polymerization in Polar Media 1. Silica Nanoparticles Encapsulated by Polystyrene. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 197, 293–308 (1998).

27. Schoth, A., Landfester, K. & Muñoz-Espí, R. Surfactant-Free Polyurethane Nanocapsules via Inverse Pickering Miniemulsion. Langmuir 31, 3784–3788 (2015).

28. Schmid, A., Tonnar, J. & Armes, S. P. A New Highly Efficient Route to Polymer‐Silica Colloidal Nanocomposite Particles. Adv. Mater. 20, 3331–3336 (2008).

29. González-Matheus, K., Leal, G. P. & Asua, J. M. Film formation from Pickering stabilized waterborne polymer dispersions. Polymer 69, 73–82 (2015).

30. Negrete‐Herrera, N., Putaux, J., David, L., Haas, F. D. & Bourgeat‐Lami, E. Polymer/Laponite Composite Latexes: Particle Morphology, Film Microstructure, and Properties. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 28, 1567–1573 (2007).

31. Oberdisse, J., Hine, P. & Pyckhout-Hintzen, W. Structure of interacting aggregates of silica nanoparticles in a polymer matrix: small-angle scattering and reverse Monte Carlo simulations. Soft Matter 3, 476–485 (2006).

32. Kosugi, K., Arai, H., Zhou, Y. & Kawahara, S. Formation of organic–inorganic nanomatrix structure with nanosilica networks and its effect on properties of rubber. Polymer 102, 106–111 (2016).

33. Keddie, J. L. & Routh, A. F. Fundamentals of Latex Film Formation, Processes and Properties. Springer Lab. 151–183 (2010) doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2845-7_5.

34. Li, S. et al. Assembly of partially covered strawberry supracolloids in dilute and concentrate aqueous dispersions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 627, 827–837 (2022).

35. Li, S., Ven, L. G. J. van der, Spoelstra, A. B., Tuinier, R. & Esteves, A. C. C. Tunable distribution of silica nanoparticles in water-borne coatings via strawberry supracolloidal dispersions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 646, 185–197 (2023).

36. Fortini, A. et al. Dynamic Stratification in Drying Films of Colloidal Mixtures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 118301 (2016).

37. Bleier, A. & Matijević, E. Heterocoagulation. Part 3.—Interactions of polyvinyl chloride latex with Ludox Hs silica. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1: Phys. Chem. Condens. Phases74, 1346–1359 (1978).

38. Balmer, J. A. et al. Unexpected Facile Redistribution of Adsorbed Silica Nanoparticles Between Latexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 2166–2168 (2010).

39. Scherer, G. W. Theory of Drying. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 73, 3–14 (1990).

40. Desroches, G. J., Gatenil, P. P., Nagao, K. & Macfarlane, R. J. Mechanical reinforcement of waterborne latex pressure‐sensitive adhesives with polymer‐grafted nanoparticles. J. Polym. Sci. (2023) doi:10.1002/pol.20230355.

41. Lewandowski et al. High Shear Pressure-Sensitive Adhesive. (2010).

Opening image courtesy of ipopba / iStock / Getty Images Plus.