STRATEGIC SOLUTIONS

The PFAS Discussion: Update 2025

Opportunities to increase market share will increase when companies are pre-positioned for growth in a resilient and scalable way.

The PFAS Discussion: Update 2025

By Lisa Anderson, Founder and President, LMA Consulting Group

By George R. Pilcher, Vice President, The ChemQuest Group, Inc.

This column provides a current snapshot of PFAS regulatory action in the United States using recent actions in the states of New Mexico, Maine, and Minnesota.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the global PFAS discussion is the suddenness with which it seems to have arisen and attracted so much attention in such a brief period of time. In 2019, the topic was of interest largely to non-specialists and a handful of forward-looking lawmakers and regulators. Within 2-3 years, the topic was on the lips of virtually everyone within the specialty chemicals industry, including: both producers and users; all politicians in national, regional, and local government; and regulators of all stripes from around the global community. This is how it seems. . . .

. . . .But the truth of the matter is more complicated. Preliminary concerns about the potential danger to human health posed by perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) were raised in the 1960s and were clearly known by 1970, at least to a few chemical companies. They were not, of course, referred to as PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) until relatively recent times, as the concept of "forever chemicals" has focused the attention of the public and, therefore, the attention of its government representatives.

In the United States, regulatory activity was taking place between 2000 and 2010 when the most-studied members of the PFAS family, such as PFOA and PFOS, were being analyzed and discussed. Nonetheless, it appears that such studies and discussions were merely serving to initiate an induction period to help prepare us for the assault now being conducted on PFAS from all sides.

Oddly enough, given its current disinterest in the topic, the earliest action in the United States was by the federal government and was centered on PFOA and PFOS, two of the most widely distributed PFAS. In 2009, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) set a federal Provisional Health Advisory Level for short-term drinking water exposure to PFOA of 0.4 parts per billion (ppb) and PFOS of 0.2 ppb. Due to widespread presence in the environment, as well as in human blood samples — and due to the highly toxic and persistent nature of these compounds — EPA took several actions to stop the use of certain PFAS in the United States. Of importance was the establishment of the stewardship program to phase out the manufacture and use of long-carbon-chain PFAS and the requirement by EPA that use of these and any other members of the PFAS family must be reported by dischargers and users to the agency.1 The final Maximum Contaminant Level Goal (MCLG) for PFOA and PFOS was lowered to “zero” for both, and the final enforceable Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) for both is 4.0 parts per trillion (ppt). A handful of other PFAS family members were also regulated at this time:

- Perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS)

o MCLG: 10 ppt

o Final MCL (enforceable): 10 ppt - Perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA)

o MCLG: 10 ppt

o Final MCL (enforceable): 10 ppt - Hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA—aka “GenX Chemicals”)

o MCLF: 10 ppt

o Final MCL (enforceable): 10 ppt

Beyond this, however, the federal government appeared to wash its hands of this issue by indicating that any further regulatory action should be undertaken by the individual states. This has, of course, led to a patchwork of potentially contradictory state regulations, since they have a number of options, including:

- Banning the use of all PFAS

- Banning the use of certain PFAS family members

- Banning the use of PFAS in certain products or product/market areas

- Banning the use of certain PFAS family members in certain products or product/market areas

- Setting limits on PFAS levels in drinking water

- Setting limits on certain PFAS family members in drinking water

For the purposes of this article, the author is going to discuss PFAS in products and articles, setting aside the subject of PFAS in drinking water with the statement that:

- Eleven states (ME, MA, MI, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT, WA, and WI) currently have standard MCLs for certain PFAS in drinking water.2

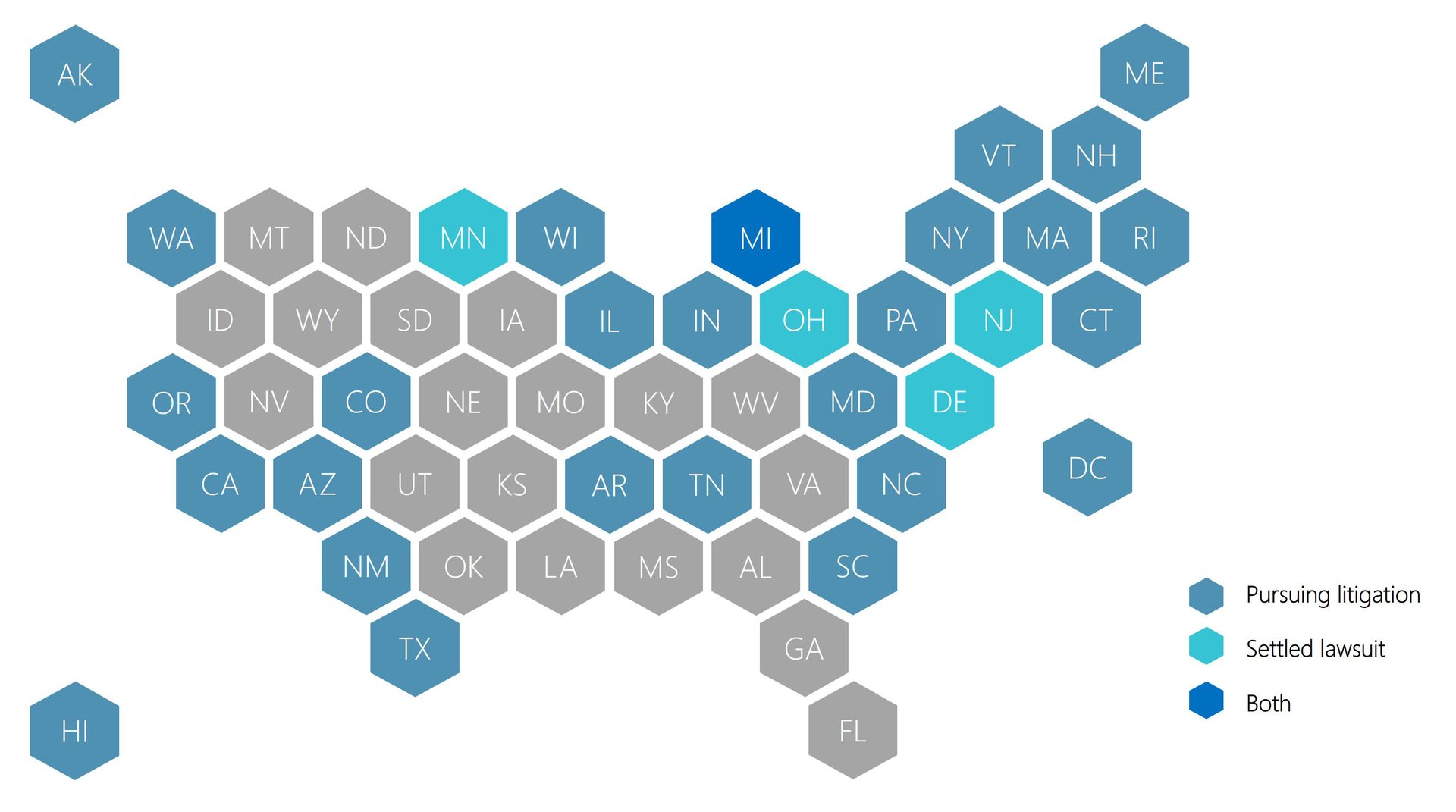

- As of December 2024, the attorneys general of 30 states and the District of Columbia have initiated litigation against the manufacturers of PFAS chemicals for contaminating water supplies and other natural resources.3 See Figure 1.

Figure 1. PFAS litigation by U.S. state attorneys general.

Current Status of Regulatory Action in the United States

First of all, a caveat: The PFAS issue is complex and dynamic. It is not possible to do full justice to this topic in a single article — nor, given the shifting sands of regulatory activity and the unusually precarious nature of actions being taken by the federal government during the first quarter of 2025, is it possible to vouchsafe the accuracy of any specific action reported in this article, other than to indicate that anything mentioned was accurate and in force at the time of its writing. The opinions offered in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of The ChemQuest Group, Inc., or of the editors of ASI or its owner, BNP Media. None of the material contained in this article is intended to represent legal advice of any kind. Anyone reading this article is advised to refer to legal counsel for clarification of any concepts addressed herein, and with regard to taking any actions suggested or implied by this article or inferred by the reader of this article.

Since each of the 50 U.S. states is taking its own regulatory approach to “intentionally added PFAS” (the author uses the term “i-PFAS” for brevity’s sake), it is simply impossible to give a state-by-state update on what categories and/or specific items are prohibited, not regulated, or exempted. Nonetheless, the reader should find that by paying attention to what a handful of proactive states have either already regulated or are in the process of regulating, one can form a reasonable understanding of the general direction in which regulation of i-PFAS-containing coatings, adhesives, and articles is trending, and take steps to prepare for both the likely and worst-case scenarios appropriately.

That said, we see ongoing PFAS regulatory activity in a number of states, as well as initial activity in others. Perhaps most importantly, at least for selected market spaces and the suppliers and manufacturers in those market spaces, certain states have now begun identifying product applications that are exempt from both prohibition as well as reporting requirements, and they appear to be establishing the trend. Summarizing briefly, three states are clearly representative of this category: Minnesota, Maine, and New Mexico. We will concentrate on these three states, led by the most recent state to take significant regulatory action:

The State of New Mexico

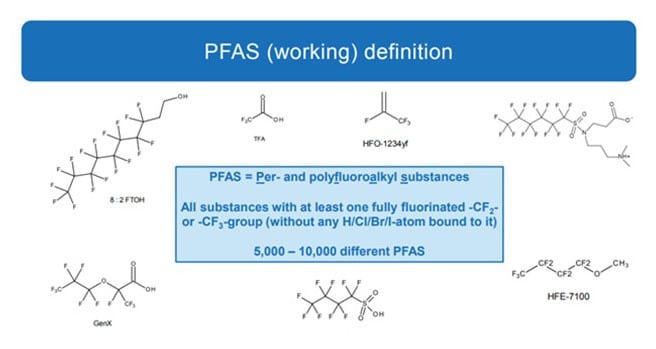

- On April 8, 2025, New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham signed the Per- and Poly-fluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Protection Act, under which this state will follow in the footsteps of Minnesota and Maine and begin phasing out certain consumer products containing intentionally added PFAS. New Mexico’s definition of PFAS is “a substance in a class of fluorinated organic chemicals containing at least one fully fluorinated carbon atom,” which is in line with most, but not all, of the definitions being used globally, and is also the definition used in this article. See Figure 2.

Figure 2. PFAS classification criteria.4

- Product(s) for which federal law governs and therefore preempts state authority

- Medical devices or drugs and the packaging of medical devices or drugs that are regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), including prosthetic and orthotic devices

- Cooling, heating, ventilation, air conditioning, or refrigeration equipment containing i-PFAS deemed acceptable for use conditions or narrowed use limits by the EPA

- Veterinary product(s) and packaging intended for use in or on animals, including diagnostic equipment, test kits, components of veterinary products, and any product that is a veterinary medical device, drug, biologic, or parasiticide or that is otherwise used in a veterinary medical setting or in veterinary medical applications that are regulated by or under the jurisdiction of the FDA; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) pursuant to the federal Virus-Serum-Toxin Act; or EPA pursuant to the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), except that any such products approved by EPA pursuant to the law for aerial and land application are not exempt

- Product(s) developed or manufactured for the purpose of public health or environmental or water quality testing

- Motor vehicle(s) or motor vehicle equipment regulated under a federal motor vehicle safety standard, as defined in 40 U.S.C. Section 30102(a)(10), except that the exemption does not apply to any textile article or refrigerant that is included in or as a component part of such products

- Other motor vehicle(s), including, but not limited to, off-highway vehicles or specialty motor vehicles, such as all-terrain vehicles, side-by-side vehicles, farm equipment, and personal assistive mobility devices

- Watercraft, aircraft, lighter-than-air aircraft, or seaplanes

- Semiconductor(s), including semiconductors incorporated in electronic equipment and materials used in the manufacture of semiconductors

- Non-consumer electronics and non-consumer laboratory equipment not ordinarily used for personal, family, or household purposes

- Product(s) containing i-PFAS with uses that are currently listed as acceptable, acceptable subject to use conditions, or acceptable subject to narrowed use limits in EPA’s rules under the Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP) Program, provided that the product(s) contains PFAS that is (are) being used as substitutes for ozone-depleting substances under the conditions specified in the rules

- Product(s) used for the generation, distribution, or storage of electricity

- Product(s) directly used in the manufacture or development of the products listed above

- Product(s) for which the NMED Environmental Improvement Board (EIB) has adopted a rule providing that the use of PFAS in that product is a CUU

- Product(s) that contain fluoropolymers consisting of polymeric substances for which the backbone of the polymer is either a per- or polyfluorinated carbon-only or a perfluorinated polyether backbone that is a solid at standard temperature and pressure

- On or before January 1, 2027, a manufacturer may not sell, offer for sale, distribute, or distribute for sale the following products containing i-PFAS: firefighting foam, cookware, dental floss, food packaging, and juvenile products.

- Also, on or before January 1, 2027, New Mexico will require manufacturers of products containing i-PFAS to report information including:

o A brief description of the product, including a UPC, SKU, or other code assigned to the product

o The purpose for which the PFAS is used in the product

o The amount of each PFAS in the product, identified by Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number® (CAS RN®), must be reported as an exact quantity determined using commercially available analytical methods; alternately, the amount of PFAS may be reported as falling within a range approved for reporting purposes by the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED)

o The name and address of the manufacturer and the name, address, and telephone number of a contact person for the manufacturer

o Any additional information requested by NMED as deemed necessary - Beginning on January 1, 2028, New Mexico will prohibit manufacturers from selling, offering for sale, distributing, or distributing for sale the following products containing i-PFAS: carpets or rugs, cleaning products, cosmetics, fabric treatments, feminine hygiene products, textiles, textile furnishing, ski wax, and upholstered furniture.

- Beginning 2032, New Mexico will prohibit products containing i-PFAS unless the use of the i-PFAS is designated as a Currently Unavoidable Use (CUU). It will also require manufacturers of products containing i-PFAS to report certain information. New Mexico will exempt certain PFAS, from both the prohibition and reporting requirements — most notably the exemptions for products containing certain fluoropolymers.5

- Also on January 1, 2032, New Mexico will join Minnesota by prohibiting products that do not contain i-PFAS, but that are sold, offered for sale, or distributed for sale in a fluorinated container or in a container that otherwise contains i-PFAS.

- In general, the products that New Mexico will prohibit, at least as of this writing, appear to be very similar to the products that Minnesota and Maine have already prohibited or will be prohibiting.

- Exemptions for the State of New Mexico: The following are exempt from both reporting and prohibition:

When all is said and done, New Mexico's exemption of fluoropolymers, which includes polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE, aka TEFLON™), seems to be based upon scientific data and reflects the logical view that such products pose no currently known risks and therefore should not be banned. We expect the majority of other states to follow New Mexico’s lead.

The State of Maine

- On January 1, 2025, Maine prohibited i-PFAS in carpets or rugs and fabric treatments, as well as fabric treatments that do not contain intentionally added PFAS but are sold, offered for sale, or distributed for sale in a fluorinated container or in a container that otherwise contains i-PFAS.

- On January 1, 2026, the State of Maine will prohibit intentionally added PFAS to cleaning products, cookware, cosmetics, dental floss, juvenile products, menstruation products, textile articles (with certain exceptions), ski wax, upholstered furniture, and products listed that do not contain i-PFAS but are sold, offered for sale, or distributed for sale in a fluorinated container or in a container that otherwise contains i-PFAS.6

- Beginning January 1, 2029, Maine plans to prohibit i-PFAS in artificial turf and outdoor apparel for severe wet conditions, unless accompanied with the following disclosure: “Made with PFAS chemicals.”

- On January 1, 2032, Maine will prohibit products that contain i-PFAS, unless there is a CUU — and it will also prohibit products that do not contain i-PFAS but that are sold, offered for sale, or distributed for sale in a fluorinated container or in a container that otherwise contains i-PFAS.

- As amended this past year, Maine will prohibit, beginning on January 1, 2040, i-PFAS in cooling, heating, ventilation, air conditioning, and refrigeration equipment, as well as in refrigerants, foams, and aerosol propellants.

The State of Minnesota

- On January 1, 2025, Minnesota prohibited intentionally added PFAS in carpets or rugs, cleaning products, cookware, cosmetics, dental floss, juvenile products, menstruation products, textile turnings, ski wax, upholstered furniture, and fabric treatments, as well as fabric treatments that do not contain i-PFAS but are sold, offered for sale, or distributed for sale in a fluorinated container or in a container that otherwise contains i-PFAS.

- As of January 1, 2026, Minnesota will require manufacturers of products containing i-PFAS to submit similar information to that listed above for New Mexico.

- On January 1, 2032, Minnesota will join Maine in prohibiting products that contain i-PFAS, unless there is a CUU — and it will also prohibit products that do not contain i-PFAS but that are sold, offered for sale, or distributed for sale in a fluorinated container or in a container that otherwise contains i-PFAS.

Where Things Stand with Regard to the Use of PFAS in the United States

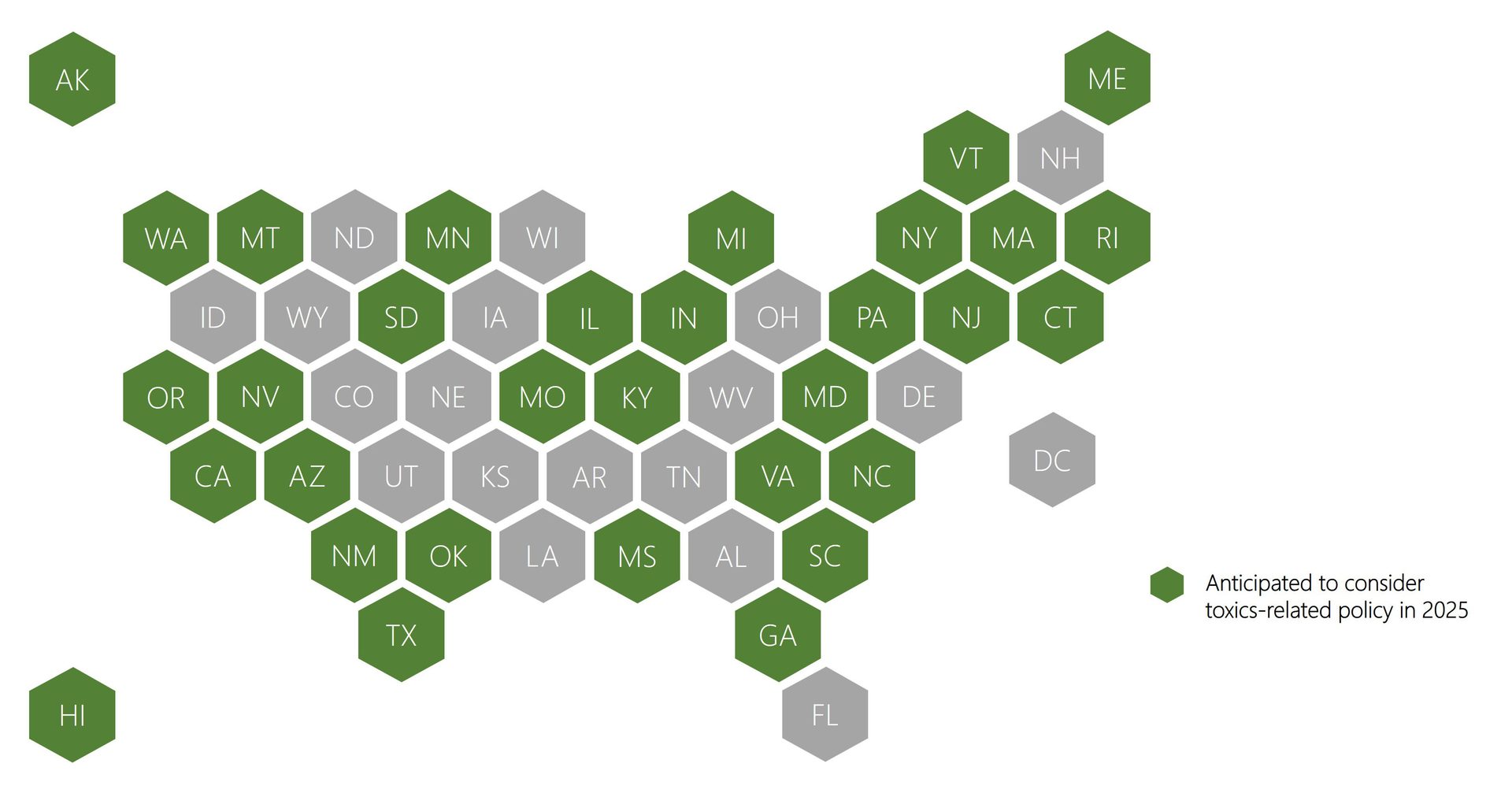

We have now seen, however, that the first 11 states in the United States have taken similar — and reasonably logical and thoughtful — steps to deal with both the concerns about the potential permanency of certain PFAS in the human body and also with the levels of PFAS contamination in the drinking water that is largely responsible for carrying PFAS into the body. It is likely that the majority of states will follow the general guidelines that have been established by these 11 states, although there are no guarantees that this will be the case.7 See Figure 3.

Also, especially given the somewhat unorthodox actions being currently taken at the federal level of government, it is possible that state legislatures and regulatory agencies may be required to revisit past PFAS regulatory activity to either conform with new federal regulations or to take advantage of reduced federal regulatory oversight.

Figure 3. States anticipated to consider toxics-related policy in 2025.

What Actions Should Specialty Chemical Producers Be Taking to Avoid “PFAS Headaches” in the Future?

For businesses that produce and sell in the United States, it makes sense to be actively replacing PFAS-based additives, unless the raw material suppliers have convincing, scientifically sound data to indicate that they will not act as “forever chemicals” in the human body. While no category of PFAS should be ignored, however, it is nonetheless reasonable, in this writer’s view, to take a cautious “wait-and-see” attitude toward PFAS polymers. It is quite possible that some of them, especially those that are used in critical applications, such as poly(vinylidene)difluoride (PVDF or PVF2), will be found to be of low concern and will either be exempted for certain uses — or possibly be free of any regulatory encumbrances of any kind.

The Bottom Line, as of Q1 2025

All producers and users of PFAS products should remain vigilant; this is not an issue where it makes sense to ignore the situation until it has been resolved by others. It is important to make sure that everyone involved is on top of the issues and determining their corporate actions based upon the direction in which regulatory actions on the issues appear to be trending. For some, this will mean finding alternative products as soon as feasibly possible; for others, it may mean patiently watching and waiting. Sitting here in 2025, however, there is no way of determining who is going to be at one end of this continuum and who is going to be at the other.

To learn more, contact the author at gpilcher@chemquest.com or visit https://chemquest.com.

References

1. “Perfluorooctanoic Acid,” Delaware Riverkeeper Network, https://delawareriverkeeper.org/issues/hazardous-chemicals/perfluorooctanoic-acid/ (accessed on 1 May, 2025).

2. Safer States, 9 January, 2025, https://www.saferstates.org/priorities/pfas/.

3. Ibid.

4. F. Averbeck, “PFAS under REACH Universal Restriction Proposal,” Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin (BAUA), 2022, https://www.asercom.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Averbeck.pdf.

5. “New Mexico Will Phase Out Products Containing Intentionally Added PFAS and Require Reporting; Exemptions Include Fluoropolymers,” Bergeson, L.L. and Hutton, C.N., The Acta Group, https://www.actagroup.com/new-mexico-will-phase-out-products-containing-intentionally-added-pfas-and-require-reporting-exemptions-include-fluoropolymers/, (Accessed 8 April, 2025).

6. Ibid.

7. Safer States, https://www.saferstates.org/resource/2025-analysis-of-state-policy-addressing-toxic-chemicals-and-plastics/.

Image courtesy of zimmytws / iStock / Getty Images Plus