FEATURE

Performances of CNSL-Based Polyurethane Technology for E-mobility

Performances of CNSL-Based Polyurethane Technology for E-mobility

By Yun Mi Kim, Senior Technical Marketing Director, Cardolite Corp., Bristol, Pennsylvania; Anbu Natesh, Vice President — Global R&D, Cardolite Corp., Bristol, Pennsylvania; Pietro Campaner, R&D Chemist, AEP POLYMERS Srl, Basovizza, Italy

Key properties of CNSL hydroxyl functional molecules were examined to identify utility of CNSL-based technology for electric vehicles (EV) battery packages.

Abstract

Cashew nutshell liquid (CNSL) is a non-food-chain biobased feedstock found in the honeycomb structure of the cashew nutshell. CNSL-based polyols, diols, and mono-ols have been evaluated in 1K or 2K polyurethane formulations to satisfy needs in E-mobility markets offering flexibility, fast cure, and excellent adhesion, and outstanding aging resistances.

In this paper, key properties of CNSL hydroxyl functional molecules were examined to identify utility of CNSL-based technology for electric vehicles (EV) battery packages. CNSL mono-ols can lower viscosity and control cure speed while diols and polyols have been used to balance strengths and flexibility of polyurethane adhesives. Improved hydrolytic stability, thermal and chemical resistance properties of CNSL-based polyols and diols support the long-term durability of battery packages. CNSL products have also shown good dielectric and fire resistance properties when evaluated in polyurethane coatings, adhesives, and foams formulations.

Introduction

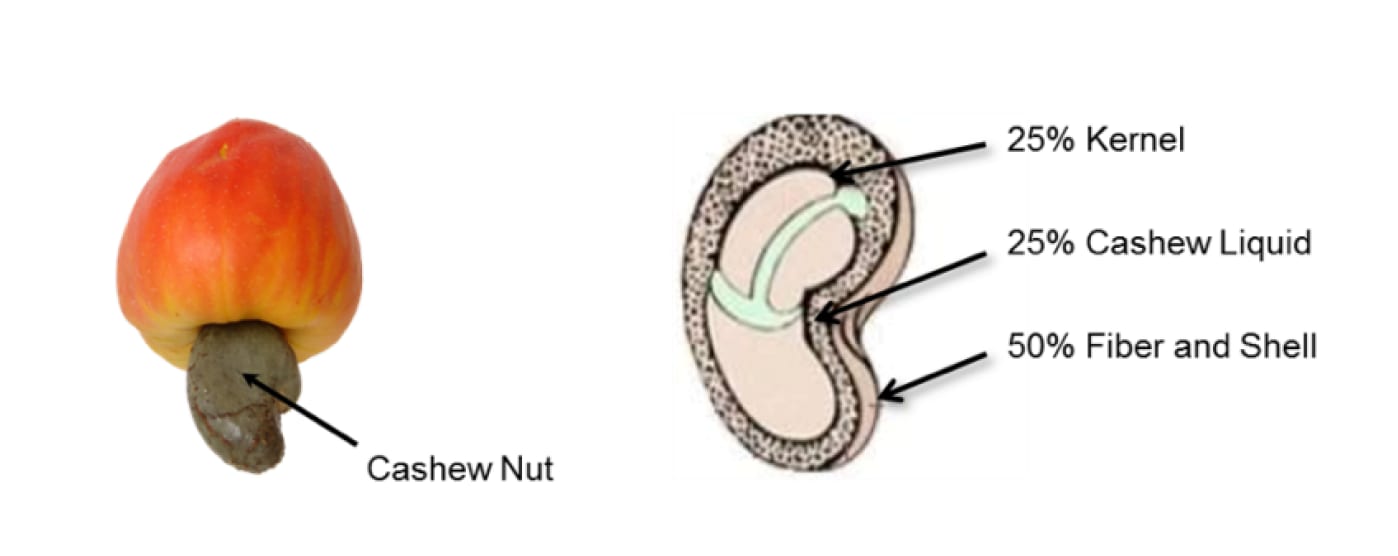

Cashew nutshell liquid (CNSL) is a bio-renewable resource found in the honeycomb structure of the cashew nutshell (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Cashew fruit and nutshell.

CNSL is a non-food-chain product that would be disposed of otherwise. One of the most commercially useful chemicals from CNSL is Cardanol, a USDA certified biobased product with 98% bio-content.

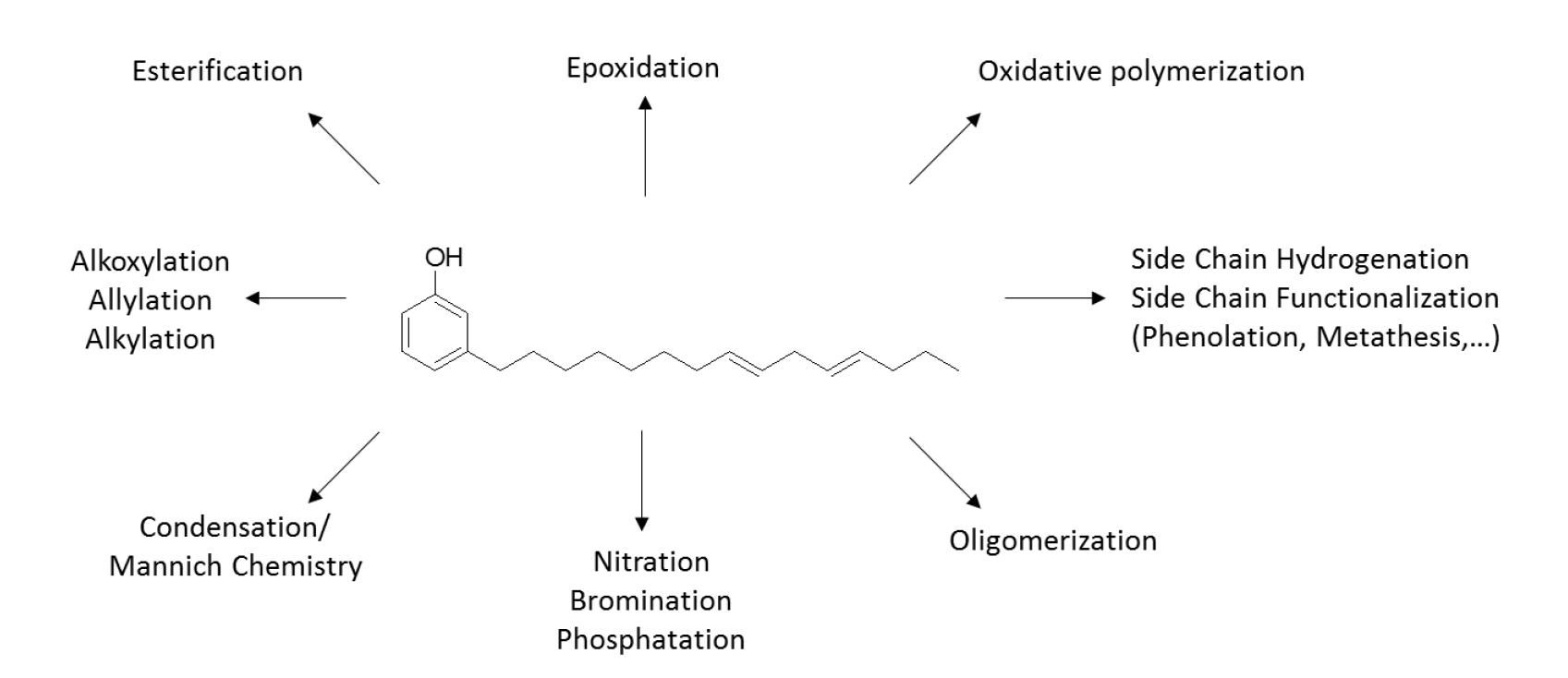

Cardanol represents an interesting and versatile monomer1, as it contains three different functional groups (the aromatic ring, the hydroxyl group, and the double bonds in the alkyl chain), that can be either selectively or simultaneously modified according to the expected features of the final product (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Cardanol’s molecule and examples of potential functionalization.

Cardanol has been used as a building block to design polyols and diols2, isocyanate blocking agents3, epoxies and epoxy curing agents4 and used as an additive for various formulations in epoxy and polyurethane5.

In E-mobility applications, various chemistries and materials have been explored and properly selected to satisfy needs in composites, coatings, and adhesives6. Use of adhesives in vehicle construction has helped to achieve weight reduction of E-vehicles by replacing mechanical fasteners and welding and by allowing the use of lighter materials such as plastics, composites, and alloy metals over heavy steel in design of battery packages and EV cars in general. Chemistries for the adhesives include epoxies, polyurethanes, silyl modified polymers (SMP), silicones, and acrylates7. Polyurethane technologies have been utilized in battery assembly because of their fast cure speed, offering high-throughput manufacturing, balanced strength and flexibility at low temperatures, excellent bond strength on many substrates, and formulation latitude to enhance durability and fire resistance8. This study will address how CNSL PU technology may provide solutions to challenges like limited operating temperature and chemical resistance.

CNSL-based polyols, diols, and mono-ols have been designed to be used in polyurethane technology with key improvements, i.e., hydrophobicity, thermal/chemical resistance. Based on the known benefits from CNSL molecules9, they have been investigated as PU adhesives in electric vehicle battery assembly adhesives and pottings. In this paper, we studied physical properties, aging resistances (hydrolytic stability, chemical resistance, and thermal resistance) and investigated feasibility of the CNSL molecules to meet fire resistance and dielectric properties. Two mono-ols from CNSL technology were examined as a diluent to control viscosity and cure speed.

Materials and Methods

Table 1 presents the typical physical properties and bio-content of Cardolite biobased mono-, di- and poly-hydroxyl functional derivatives that have been selected for the present study.

Table 1: Physical properties of Cardolite mono-ols, diols and polyols.

Viscosity, hydroxyl value, acid value, and water content measurements on the different polyols were performed according to ASTM D4878, ASTM D4274, ASTM D4662, and ASTM D4672, respectively.

GPC analysis for cardanol-based polyols molecular weight characterization and functionality determination was performed on the same HITACHI HPLC-GPC systems, isocratic mode (0.5 ml/min flow rate; wavelength set to 280 nm). Three columns connected in series (Tosoh TSKgel Super H1000, Tosoh TSKgel Super H2000, Tosoh TSKgel Super H3000, 3 µm, 6x150 mm; mobile phase: tetrahydrofuran) or a single column (Tosoh TSKgel G3000, 5 µm, 7.8x330 mm; tetrahydrofuran, buffered with 0.25% TFA and 0.25% TEA) thermo-stated at 40 °C were used. Eleven narrow MW polystyrene standards have been used for the calibration curve.

Test specimens and results are obtained based on the following ASTM methods: tensile strength/elongation (ASTM D638), and chemical resistance (ASTM D6943), Shore D/A hardness (ASTM D2240), and lap shear strength (ASTM D1002). All the adhesives were prepared by curing with polymeric methylene diphenyl diisocyanate (PMDI) at NCO index 100 at various curing conditions. Each cure condition was selected based on specimen and test items.

Flexible polyurethane foams were prepared using toluene di-isocyanate (TDI 80/20) and characterized accordingly to ASTM D3574 for their physical properties, while horizontal UL-94 and CAL 117 (Section A, Part I vertical burning test) have been used to run fire resistance tests.

Results and Discussion

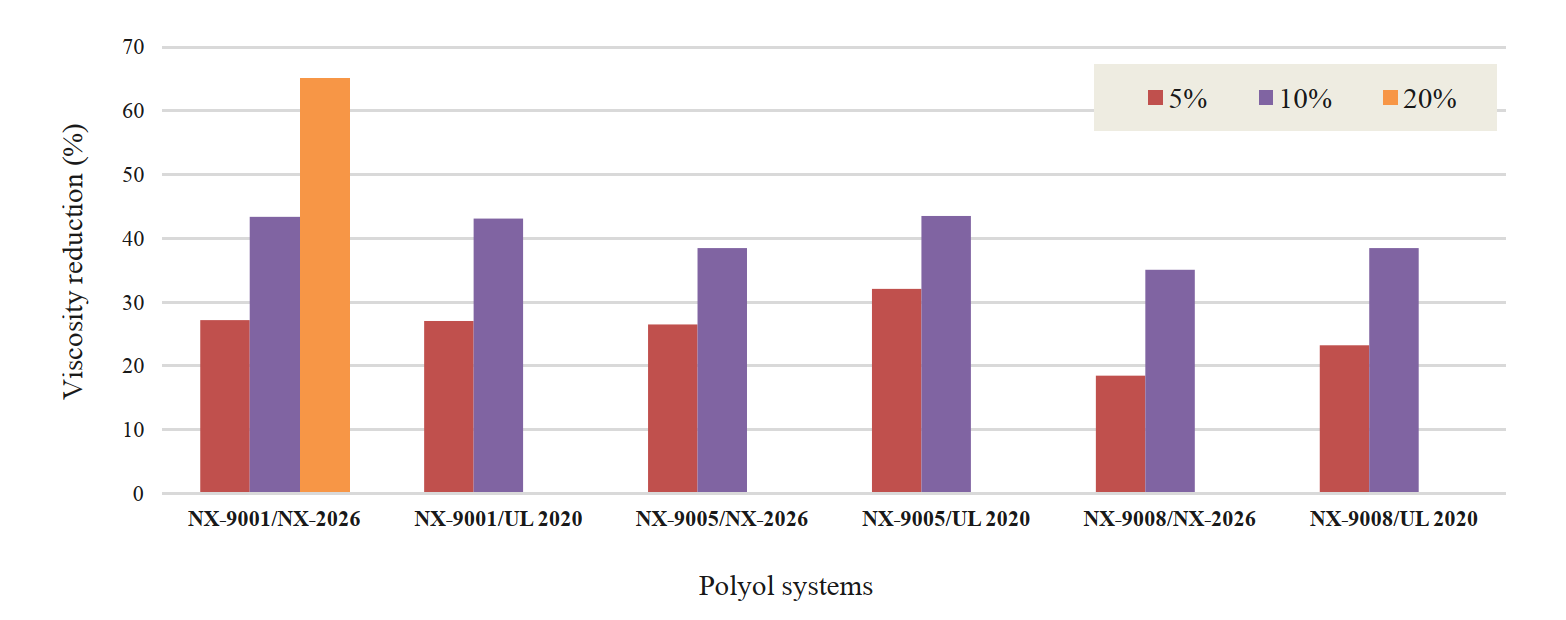

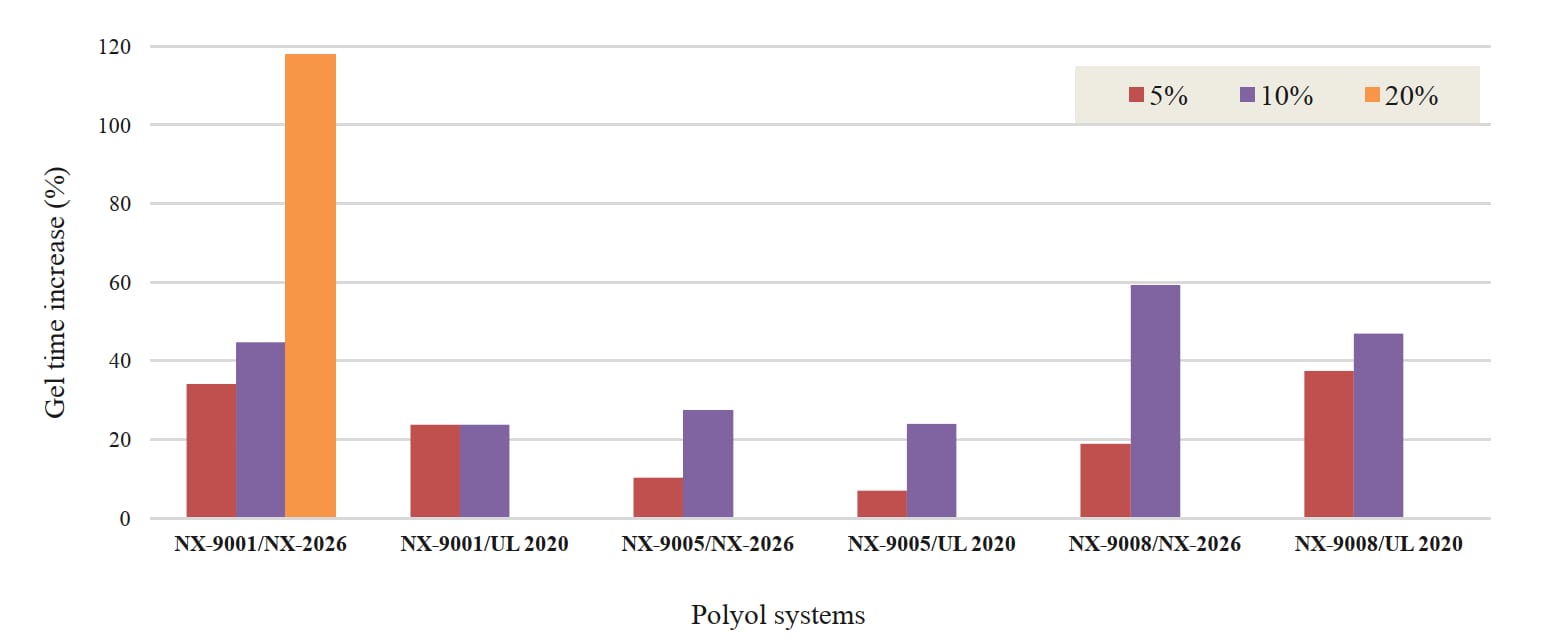

Cardanol (NX-2026) and mono-ethoxylate CNSL (Ultra LITE 2020) were added to polyols at different use-levels to understand their dilution efficiency (Figure 3) and cure speed effect (Figure 4). CNSL diluents can lower viscosity up to 30% at 5% use-level and 40% at 10% use-level. Cure speed effect was studied by looking at gel time. The polyol blends were cured with PMDI at NCO index of 100 at room temperature. Longer gel times were achieved by incorporating the CNSL diluents, offering maximum 37% and 59% increase in gel time at 5% and 10% use-levels, respectively. In later studies, we also investigated impact on strengths and Tg of the diluents.

Figure 3: Mono-ols: dilution performance

Figure 4: Cure speed effect of cardanol-based mono-hydroxyl functional derivatives NX-2026 and UL-2020

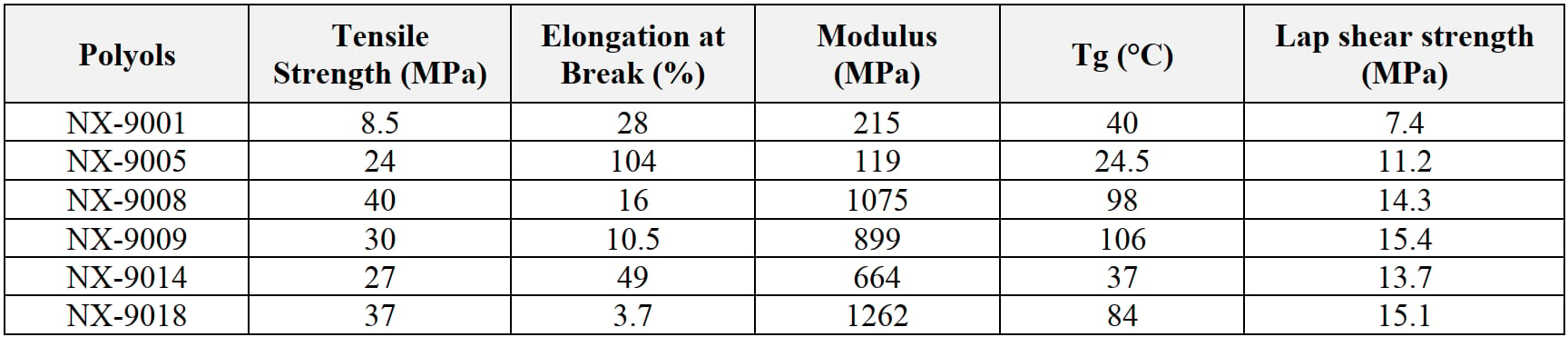

Adhesives for EV battery assembly require well-balanced physical properties. Key ingredients include high functional polyols for strengths, diols for flexibility, and mono-ols for lowering viscosity in the case of filled formulations and for maintaining strength and flexibility. As evident from the tensile strength, elongation, and bond strength on sand-blasted steel, and Tg results of Cardolite polyols reported in Table 2, NX-9008, NX-9009, NX-9018 are high-strength polyols, while NX-9005 offers excellent flexibility.

Table 2: Physical properties: strengths, flexibility, Tg, bond strengths (cured at 25 °C /16hr + 70 °C /4hr + 120 °C /2.5hr).

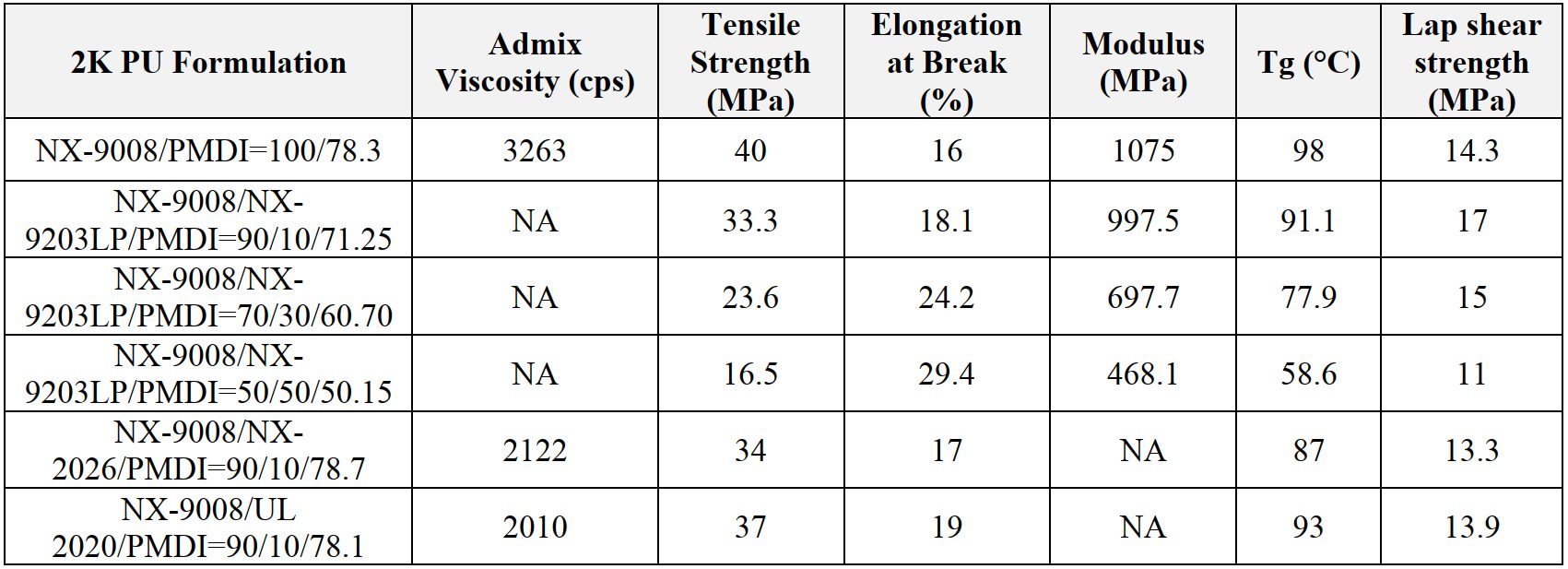

Among the different grades, NX-9008 shows the highest mechanical and thermal properties, but its medium viscosity (around 3000 cps @ 25 °C) and high modulus could potentially limit its usability in systems where lower viscosity and a certain flexibility are preferred. For this reason, the effect of NX-9203LP diol and mono-ols addition to NX-9008 has been studied (Table 3). As a result, 10% of the mono-ols helped lower the viscosity while maintained high strength, good adhesion and Tg; at the same time, blending NX-9203LP with NX-9008 provided increased flexibility and maintained good lap shear strength.

Table 3: Effect of physical properties using diols and mono-ols in 2K PU.

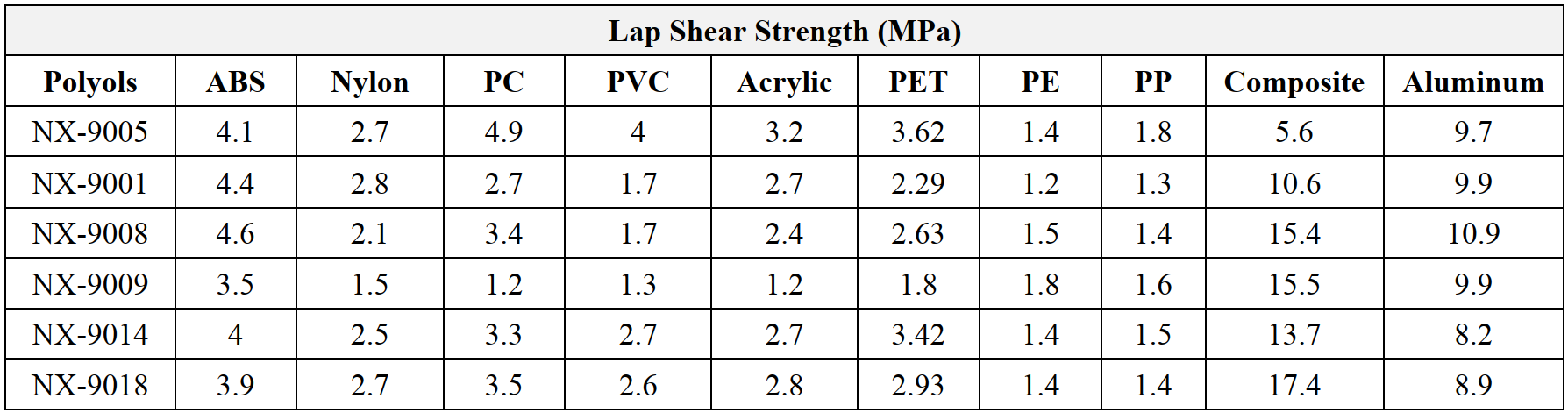

One of ways to achieve weight reduction on battery packages is to use plastics, composites, and aluminum. This observation prompted the evaluation of adhesion performances of the same polyols listed in Table 2 on other substrates, selected among plastics, composite, and aluminum (Table 4). Overall, NX-9005 exhibited best adhesion on plastics while NX-9008 showed excellent adhesion on aluminum, ABS, and composite.

Table 4: Lap shear strength on plastics, composite, and Aluminum (cured at 60 °C/72hrs).

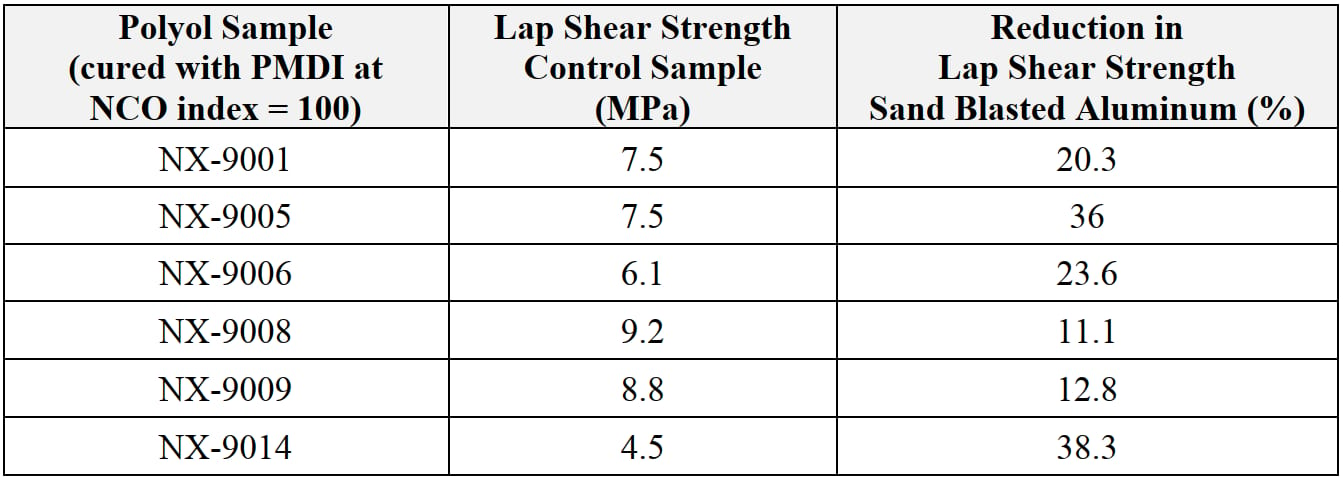

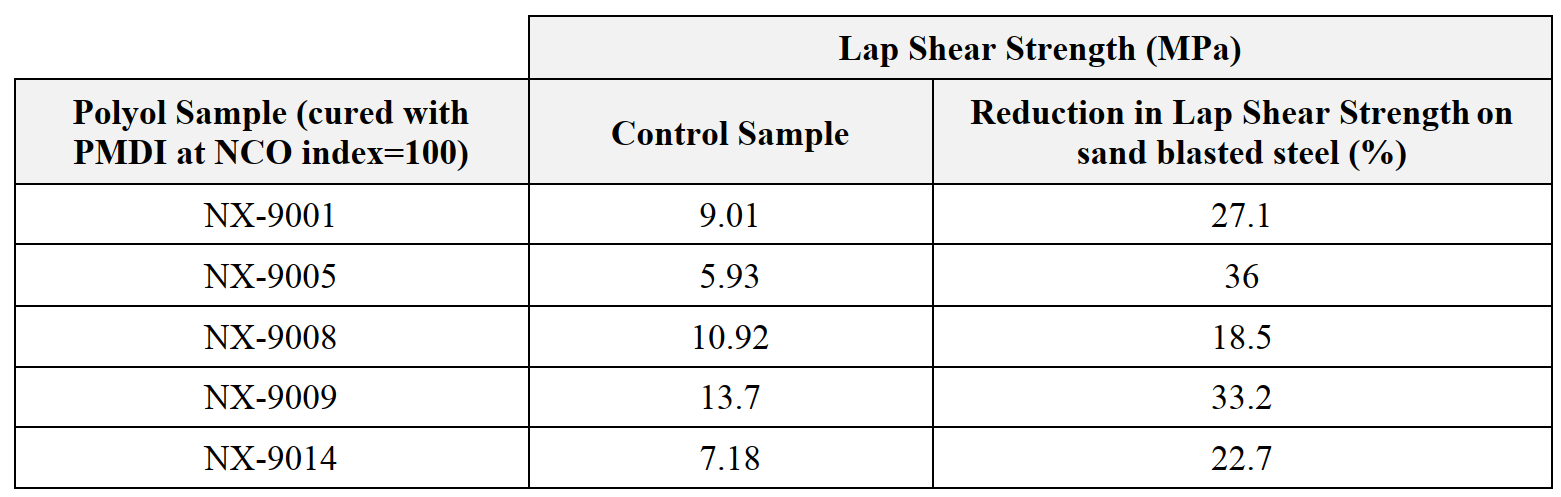

Adhesives used in EV battery assembly require very rigorous qualification process. Among all tests, aging resistances under various harsh conditions represents one of the key items. The typical requirement is to maintain its strength at 70% minimum after being exposed to demanding conditions to determine the durability of the adhesives. The industry standard hydrolytic stability test method has been 85 °C/85%RH for greater than 1000 hrs exposure, but for internal screening purpose, we employed 80 °C /7 days immersion conditions with the lap shear specimen. The performance of hydrolytic stability of the adhesives (Table 5) NX-9008 and NX-9009 systems exhibited the least adhesion decrease, followed by NX-9001, therefore allowing the assumption that good hydrolytic stability can be achieved when PU systems with high strength and good water resistance are used.

Table 5: 80 °C /7days hydrolytic stability (cured at 60 °C /72hrs).

In terms of alkaline resistance (Table 6), NX-9008 has shown the best performance, followed by NX-9014 and NX-9001.

Table 6; Alkaline resistance (10% NaOH 14 days immersion), cured at 60 °C /72hrs.

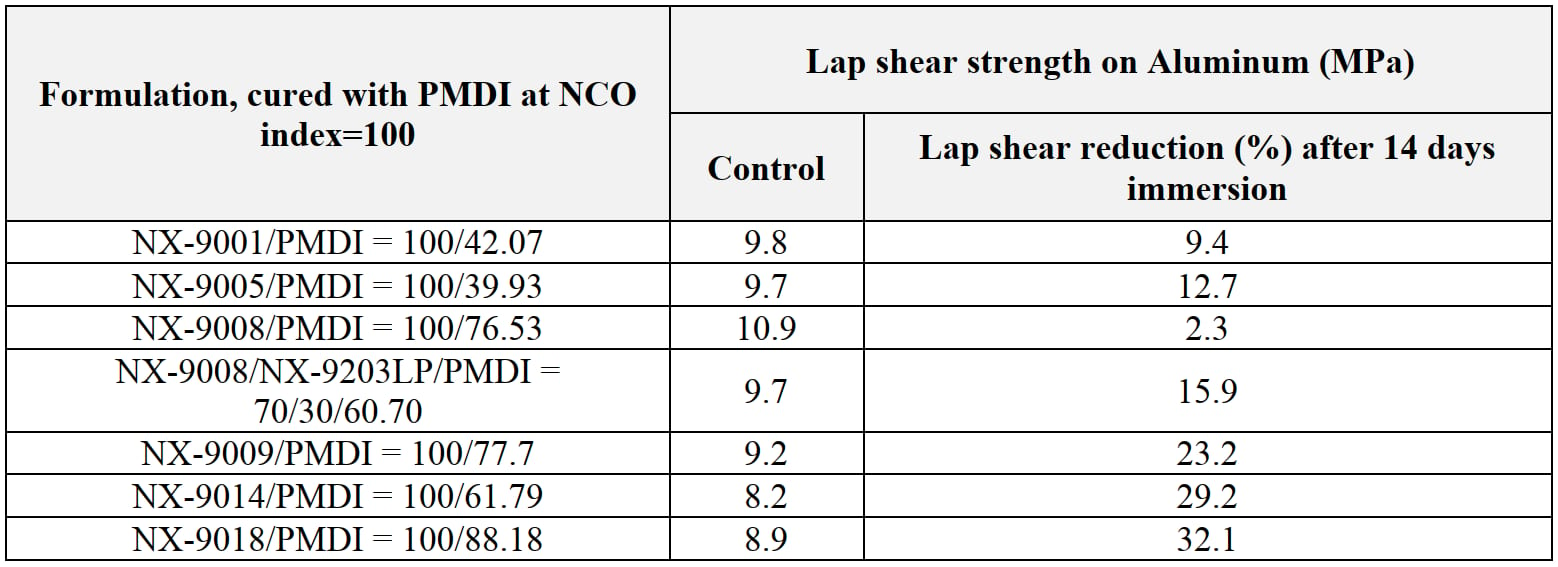

In order to expand the study and confirm the versatility of the polyols described above, an ethylene glycol/water blend was prepared and used as testing media to understand how typical coolant can impact adhesion upon 14 days immersion (Table 7). Amongst tested PU systems, NX-9008 displayed the best resistance to the coolant exposure followed by NX-9001 and NX-9005.

Table 7: Chemical resistance (Ethylene glycol/water = 50/50 mixture/14 days), cured at 25 °C/16hrs + 70 °C/4 hrs + 120 °C/2.5 hrs).

Since CNSL-based molecules are known for improved thermal resistance and chemical resistance due to the aromatic group in the backbone, another part of the test plan has been focused on tensile strength, elongation and Tg variation upon exposure to 135 °C/1000 hrs (Table 8). However, polyurethane systems are not typically known for high temperature durability [10], thus, we decided to limit temperature to be max 135 °C.

Table 8: Thermal stability after 135 °C /1000 hrs exposure.

It is observed that the tested PU systems exhibited increased tensile strength, reduced elongation, and reduced Tg after 135 °C/1000 hrs. However, NX-9008 showed increased Tg and the least changes overall after the high-temperature exposure. Based on the given aging test results, NX-9008 seems to be the most suitable polyol for EV battery assembly adhesive formulation, offering improved durability and strengths, followed by NX-9001.

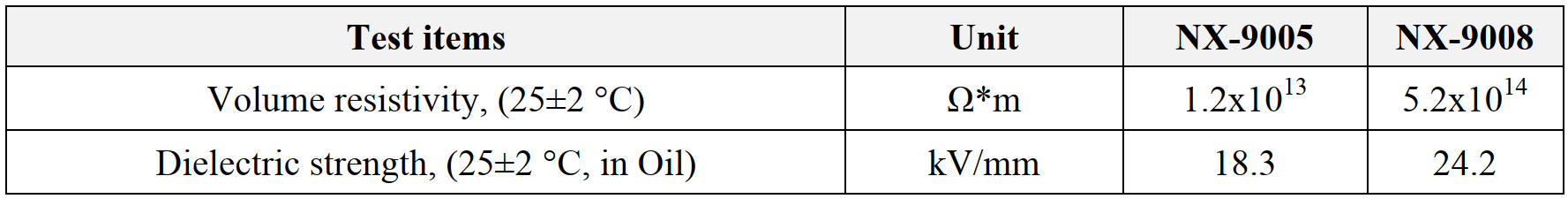

Opportunities for 1K or 2K polyurethane technology in potting applications for electronics and EVs have been growing because of the ease of cure and satisfying physical properties of PU materials. With these premises, selected polyols were then examined for their durability and processability (Table 9) and for dielectric properties (Table 10).

Table 9: 2K PU for water resistance, thermal shock and exotherm.

Table 10: Dielectric properties.

In comparison to epoxy systems, PU systems have offered better thermal shock resistance due to their good flexibility and low exotherm. NX-9001 and NX-9014 offered good thermal shock performance, while NX-9001 and NX-9007 exhibited better water resistance. General requirements in dielectric properties in EVs include dielectric strength of greater than 10 kV/mm and volume resistivity of greater than 1.0x1014 Ω. m. NX-9008 exhibited most suitable dielectric properties for EV pottings, while NX-9005 satisfied dielectric strength requirements.

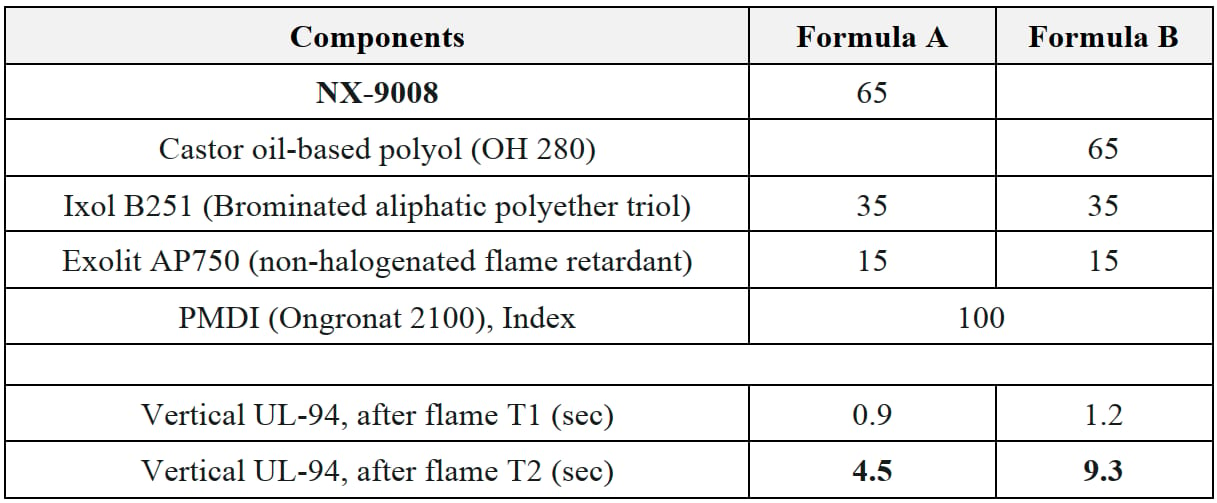

Materials used in EV battery packages need to meet a basic fire resistance requirement, UL94 V0 (burning stops within 10 secs). To improve fire resistance through thermal managing, thermally conductive adhesives are commonly used in the battery packages, while thermal conductivity is controlled by specific fillers, such as alumina, boron nitride, and fire resistance is achieved by use of fire retardants. To implement the study, we then formulated polyurethane adhesives with two different types of fire retardants and compared performance of CNSL polyol (NX-9008) against a castor oil-based polyol, selected as a benchmark not only for its bio-derived chemical backbone, but also for comparable OH value.

Table 11: Fire resistance study.

Both formulations passed the UL-94 VO requirement. It is understood that polyols are not a key ingredient for meeting UL-94 V0; however, we observed that CNSL polyol NX-9008 helped to enhance its fire resistance by offering significantly shorter after-flame T2 (Table 11).

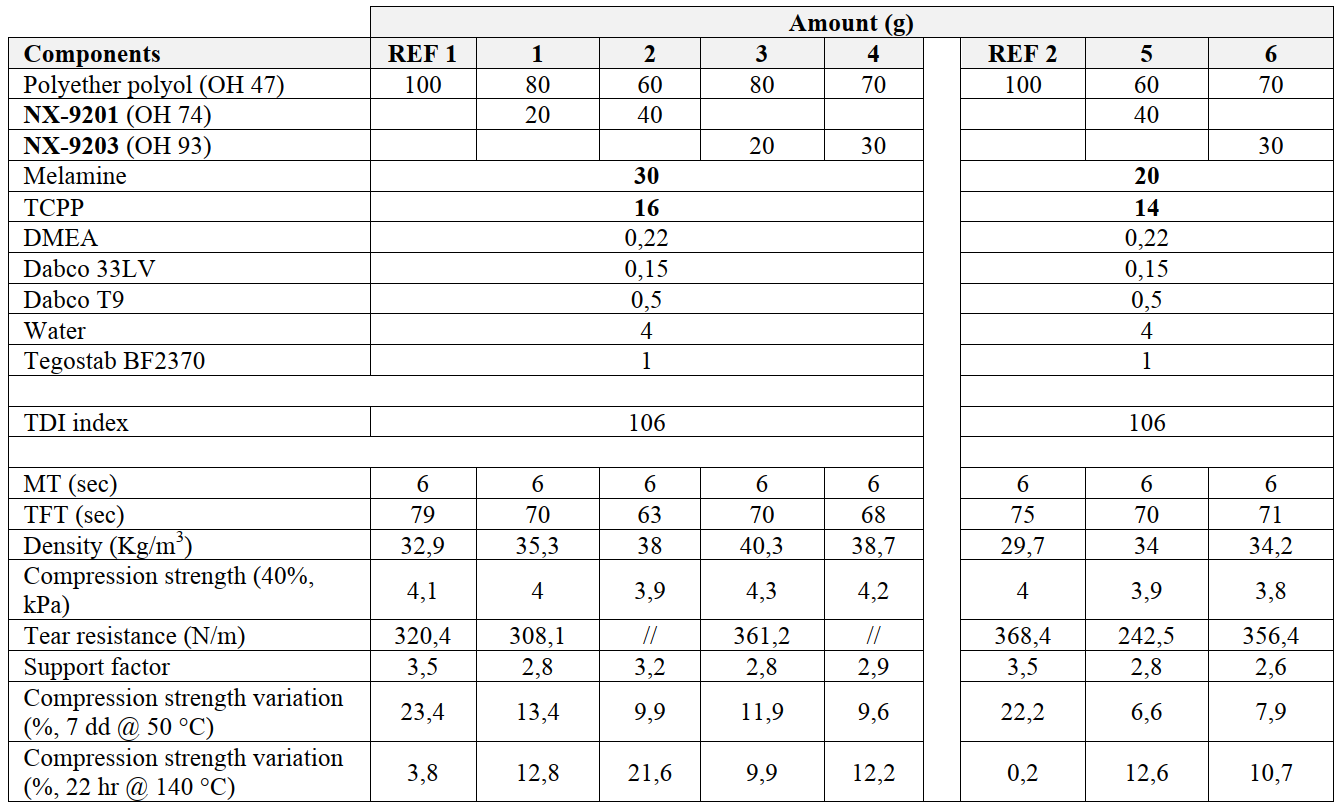

To exploit the potential applicability of cardanol-based hydroxy-functional derivatives in polyurethane systems for automotive applications (e.g. car seats) and confirm the versatility of cardanol-chemistry, two of the cardanol-based polymeric diols described in Table 1, namely NX-9201 and NX-9203, have been tested in a reference flexible PU foam formulation. Given their chemical backbone (presence of aromatic ring) and hydroxyl value (higher than the one commonly used in the formulation of flexible PU foams), these two grades have been introduced only as partial replacement of a high-molecular-weight polyether triol (Table 12).

Table 12: performances of cardanol-based polymeric diols NX-9201 and NX-9203 in a reference flexible PU foams.

In particular, NX-9201 and NX-9203 have replaced at maximum 40% and 30% of the reference polyether polyol, respectively (NX-9203 is characterized by higher aromatic content than NX-9201, so its overall more rigid chemical backbone doesn’t allow higher dosages without incurring a negative impact on final flexibility). Both cardanol-derivatives exhibit faster reactivity (shorter gel time than reference), with final mechanical properties not too far from the reference.

As in the case of PU adhesives, one of the main benefits imparted by the introduction of cardanol-derivatives in flexible PU foams is an increase in hydrolytic stability, as evident from the lower compression strength variation values recorded after having immersed foams in distilled water for 7 days at 50 °C.

When aged upon heating (22 hrs storage at 140 °C), cardanol-based foams show an increase in compression strength, with a variation higher than the fully polyether-based systems. This effect can be explained by the presence of unsaturations in cardanol's C15 side chain in cardanol-polymeric diols, that can partially crosslink at high temperatures, causing an increase in crosslinking density and a subsequent slightly higher compression strength.

At the same time, cardanol derivatives are characterized by a certain aromatic content (depending on cardanol amount in each polyol backbone); in particular, NX-9201 has an aromaticity around 5.2%, while NX-9203 is around 17.5%. For this reason, an adjustment of flame retardants loads has been made, reducing melamine and TCPP from 30 parts and 16 parts, respectively (Formula REF. 1, 1, 2, 3, 4), to 20 parts and 14 parts (Formula REF. 2, 5, 6), without affecting the overall performances.

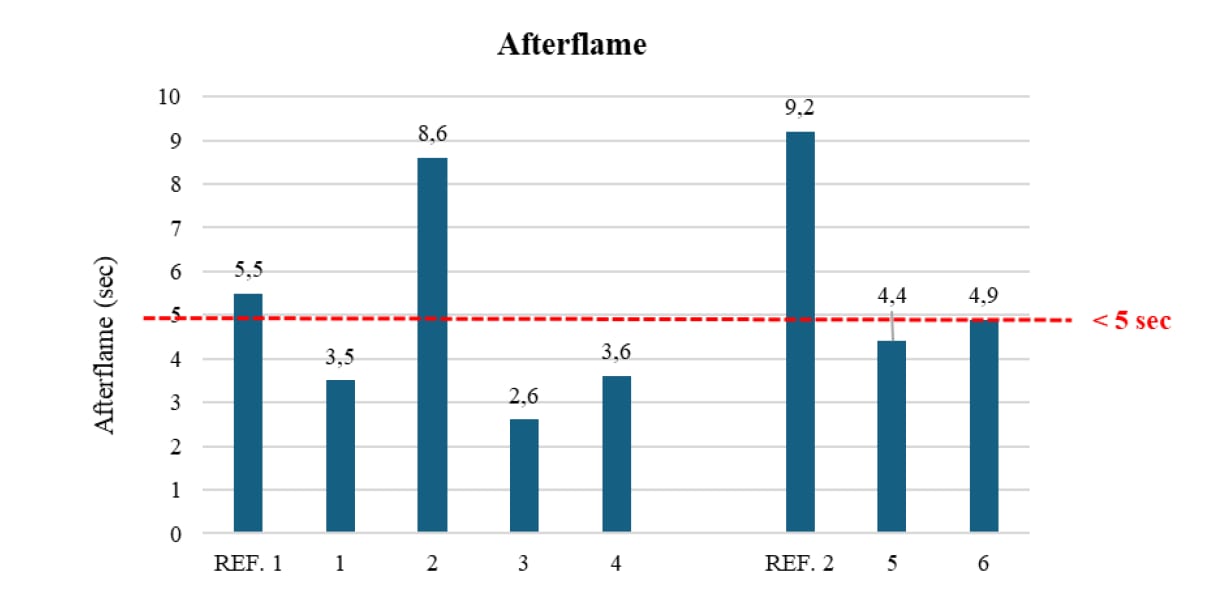

All the resulting foams have been then tested for their fire resistance performances according to CAL 117 (Section A, Part I vertical burning test), collecting after-flame (Figure 5), and char length (Figure 6) values.

Figure 5: after-flame values (according to CAL 117, Section A, Part I, vertical burning test) of flexible PU foams as in Table 12.

Figure 6: char-length values (according to CAL 117, Section A, Part I, vertical burning test) of flexible PU foams as in Table 12.

To fulfill the requirements of the specific fire test method used in the study, after-flame and char length values must be lower than 5 seconds and 14,7 cm, respectively.

As evident from the two graphs, the introduction of cardanol-polymeric diols, in general, significantly contributes to a reduction of both testing items, still providing good values even in the presence of a reduced amount of flame retardants.

Conclusions

In this study, we identified the utility of CNSL polyols, diols and mono-ols in EV adhesives and potting, along with preliminary encouraging results in flexible PU foams. CNSL mono-ols can be used for lowering viscosity while maintaining strengths and Tg, while cardanol-derived polymeric diols offer increased flexibility, excellent hydrolytic stability, not only in PU adhesives and potting, but also in flexible PU foams, where they also showed a good potential to improve fire resistance. At the same time, aging resistance studies, dielectric properties, and fire resistance test results suggest that NX-9008 is a suitable polyol for polyurethane EV adhesives and potting formulations.

Acknowledgements

"Performances of CNSL-Based Polyurethane Technology for E-mobility" 2024 Polyurethanes Technical Conference 30 September–2 October, 2024, Atlanta, GA, USA, Published with permission of CPI, Center for the Polyurethanes Industry, Washington, DC.

References

1. a) Anilkumar, P. Cashew Nut Shell Liquid: A goldfield for functional materials Springer International Publishing AG 2017; b) Voirin, C.; Caillol, S.; Sadavarte, N. V.; Tawade, B. V.; Boutevin, B.; Wadgaonkar P. P. Polym. Chem., 5, 3142, 2014

2. a) Bhunia, H.P.; Nando, G.B.; Chakia, T. K.; Basak, A.; Lenka, S.; Nayak, P.L. European Polymer Journal, 35, 1381, 1999; b) Ionescu, M.; Wan, X.; Bilić, N.; Petrović, Z., S. J. Polym. Environ., 20, 647, 2012

3. a) Campaner, P.; Kim, Y. M.; Tambe, C.; Natesh, A. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. 7, 2, 1642, 2020; b) Campaner, P.; Dinon, F.; Tavares, F.; Kim, Y. M.; Natesh, A. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. 7, 4, 1904, 2021

4. a) Wazarkar, K.; Sabnis, A. Prog. Org. Coatings 118, 9, 2018; b) Ma, Z.; Liao, B.; Wang, K.; Dai, Y.; Huang, J.; Pang, H. RSC Adv., 6, 105744, 2016; c) Mora, A.S.; Decostanzi, M.; David, G.; Caillol, S. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 121, 8, 1800421, 2019

5. Reese, J. R.; Moore, M. N.; Wardius, D. S.; Hager, S. L. EP1930355

6. a) Wazeer, A.; Das, A.; Abeykoon, C.; Sinha, A.; Karmakar, A. Green Energy and Intelligent transportation, 2, 100043, 2023; b) Mohanty, A.K.; Vivekanandhan, S.; Tripathi, N.; Roy, P.; Snowdon, M.; Drzal, L.T., Misra, M. Composites Part C 12, 100380, 2023

7. Cavezza, F.; Boehm, M.; Terryn, H.; Hauffman, T. Metals, 10, 730, 2020

8. a) Akindoyo, J. O.; Beg, M.D.H.; Ghazali, S.; Islam, M. R.; Jeyaratnam, N.; Yuvaraj, A.R. RSC Adv, 6, 114453, 2016; b) Golling, F.E.; Pires, R.; Hecking, A.; Weikard, J.; Richter, F.; Danielmeier, K.; Dijkstra, D. Polymer International, 68, 5, 848, 2018

9. Kim, Y.M: Natesh, A.; Campaner, P.; Hong, X. CPI Polyurethanes Technical Conference 2022, Proceedings of 2022 CPI Conference, National Harbor (MD), October 3-5, 2022

10. Ketata, N.; Sanglar, C.; Waton, H.; Alamercery, S.; Delome, F.; Raffin, G.; Grenier-Loustalot, M.F. Polymers & Polymer Composites, 13, 1, 1-26, 2005

Opening image courtesy of quangpraha / iStock / Getty Images Plus.